During finals week last December, Helen Meigs ’21 decided to ditch her schoolwork and travel to Washington, D.C.

A new Democratic majority had been elected to the House of Representatives, and Meigs wanted the chance to witness history as a diverse crop of freshman lawmakers like Ilhan Omar and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez were sworn into office. But she also wanted to lend her voice to a chorus of nearly 1,000 young people from around the country who were gathering to demand that the 116th Congress do what its predecessors had failed to do: halt the pace of carbon emissions and commit to building a greener and more sustainable economy.

“I had this whole big internal quandary asking myself whether I should risk my grades and go on this trip, or if I should stay on campus and concentrate on my schoolwork,” says Meigs, an international studies major and environmental studies minor from Portland, Oregon. “But in the end, I realized I just had to go, because if we don’t solve this climate emergency, then what does my GPA even matter?”

Meigs is part of Macalester’s chapter of the Sunrise Movement, a national youth-centered campaign to move America to 100 percent clean energy by 2030 and to make climate change the leading issue of the 2020 presidential campaign. Though she’s always had an interest in social justice issues and the great outdoors, Meigs never expected that concern about the climate would come to dominate her college experience. But when the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a special report in October 2018 warning that in just 12 years, the planet could reach a tipping point from which it may never return, Meigs—like many in her generation—quickly found her calling.

“I had the realization that if we don’t solve this crisis, every other issue and injustice around the world will be exacerbated by the changing climate,” she says. “It’s beginning to feel like thinking about our futures is pointless if we don’t solve this problem. This is not something I intended to do when I came to Macalester, but when I think of what I’ll do when I graduate, I just can’t picture myself doing anything other than trying to stop this crisis.”

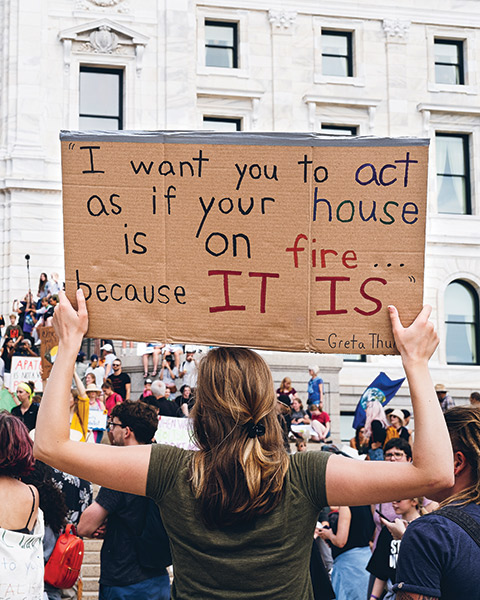

A group of Mac students rallied with 6,000 Youth Climate Strike attendees at the Minnesota State Capitol in September 2019. Photo by Kori Suzuki ’21.

A New Degree of Urgency

Worries about what will happen to a warming planet aren’t confined to college campuses. In fact, headlines about extreme hurricanes, catastrophic fires, melting sea ice, and other signs of our climate crisis have given rise to new words like “solastalgia,” a neologism to describe the pain of living in a threatened environment. Mental health professionals also use the terms “eco-anxiety” and “climate grief” to describe a deep sadness about the landscapes and resources already at risk, as well as a distressing sense of powerlessness about preventing many of the worst-case scenarios the scientific community predicts. While this anguish affects people of all ages, the rise of high-school activists like Sweden’s Greta Thunberg, and the success of recent youth climate strikes around the globe, suggest that Generation Z is especially hard hit by these anxieties. In fact, a 2019 Gallup poll found that 54 percent of 18- to 34-year-olds worry “a great deal” about global warming, while only 38 percent of those aged 35 to 54 share the same concerns.

“Adults have trouble understanding climate change in its radical sense, which is that it’s the greatest global health threat of the twenty-first century,” says Bruce Krawisz ’74, a retired physician who now researches and writes about the health effects of climate change. “But when you talk to younger people, they get it—and they have reason to be worried.”

Environmental studies and psychology professor Christie Manning, who teaches a course called “Psychology and/of Climate Change,” says that while the scientific literature about “climate anxiety” is just beginning to emerge, she and her colleagues see anecdotal evidence of the condition every day. It comes from students who question whether it’s ethical to have children or wonder if they really have time for graduate school if the predictions about a 2030 tipping point prove true. “Another thing I observe in my classes is the confusing disconnect between the scientific data telling us what’s happening, and the beautiful fall day with blue skies and the nice breeze,” she says. “The signals we’re getting from science don’t match the signals we may be getting from the world.”

That disconnect is even more pronounced in the world of politics, where Donald Trump’s election in 2016, and America’s subsequent retreat from the historic Paris climate accord and other environmental protections, suggest there’s little political will for turning the tide. “When people in power are saying, ‘Calm down, quit worrying,’ that actually magnifies the distress for many young people,” Manning says. “The data say we should be taking action now, but that’s not necessarily what students are seeing from the adults in their lives.”

“Frustration really isn’t a deep enough word to describe how students are feeling about their future,” says Roopali Phadke, environmental studies professor and chair, who believes the political climate may be fueling students’ growing interest in coursework that connects to climate change. To meet the demand, her department offers a specialized study path devoted to climate change and policy, while many departments are featuring climate-related content in courses such as “Moral Psychology,” “Language and Climate,” “Energy Justice,” and “Environmental Politics and Policy.” “We’re seeing more and more students attracted to these classes—in part because climate is so interdisciplinary, but also because they’re not only interested in learning about climate science,” Phadke says. “They want to connect that with the tools to change the policies that we have in place.”

In fact, while climate issues in the media can often divide along partisan lines, among Macalester students there’s consensus that the status quo is no longer sustainable, says political science instructor Michael Zis, who helped design a “Sustainability for Global Citizenship” seminar and taught “Environmental Politics and Policy” this past fall. “What I’ve observed is that there’s no room for skepticism anymore. Even among the most conservative students, the debates are not about the science, or whether climate change is happening, but over the merits of competing paths proposed to address it.

“But what I’m also seeing is a shift toward greater support for more radical or drastic action,” he says. “A few years ago, you might have heard students express support for privatized or marketbased or incremental solutions, but with the climate strikes we’re seeing and the Greta Thunberg effect, there’s a lot more interest in protest and public acts that can move the needle.”

Climate strike attendees fill the capitol rotunda. Photo by Kori Suzuki ’21.

Activism Over Anxiety

To cope with climate anxiety, mental health professionals often recommend becoming more active in the search for solutions—an approach to self-care that seems to be part of Macalester’s DNA. “I have to laugh when I hear that because at least a few of my students say activism is what they really do at Macalester, and they fit their classes in around that,” says Manning.

One of the most visible signs of student climate activism has been the Fossil Free Mac (FFM) movement, a student-led initiative urging the Board of Trustees to divest from private oil and gas partnerships over the next 15 years. In response to FFM and the college’s Social Responsibility Committee proposal, the board voted in October to continue and expand work to reduce Macalester’s carbon footprint, and to approve new investments in private oil and gas partnerships only when the Investment Committee believes the investment is reasonably likely to result in a net reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

“It took seven years for that one step,” says Sasha Lewis-Norelle ’21 (Madison, Wis.), one of the students who led the charge. Though he’s frustrated Macalester hasn’t joined the ranks of universities and colleges that have committed to full divestment, he’s inspired to do more when he graduates. “I’d love to keep working in environmental justice, and Macalester has taught me to think more critically about things,” he says. “I think those skills are going to be really important when we’re dealing with issues as intricate and systemic as climate change.”

Challenging existing systems in innovative ways is another approach Macalester students are applying to environmental challenges, says Margaret Breen ’20 (Minneapolis). She’s a member of the Youth Climate Intervenors, a group of Macalester students working to oppose Line 3, a proposed tar sands oil pipeline through northern Minnesota. Making the case that their generation will be disproportionately affected by climate change, and the environmental damages that would be caused by a tar sands oil pipeline spill, the group petitioned for and earned party status by the Public Utilities Commission in 2017. While the state Supreme Court just declined a request to hear indigenous and environmental groups’ complaints about Line 3’s environmental review process, the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency denied a key water permit for the pipeline. Those losses and wins are teaching Breen and her teammates what it takes to be effective climate activists for the long haul.

“Worrying about the future can be paralyzing, because there’s this feeling that nothing we can do is bold or impactful enough,” she says. “But it’s been really empowering and exciting for me to be part of a community of people imagining what climate justice will look like, and learning where I’ll need to focus my energy in the future.”

Major youth-led climate strikes have also mobilized large numbers of Mac students and recent graduates, including Marco Hernandez ’19, who spoke on the steps of the Minnesota State Capitol during a September 2019 climate strike that was expected to attract 2,000 students. Instead, more than 6,000 attended. “I spoke about how I’m originally from Richmond, California, where the second-largest refinery in the state of California resides,” he says. When the refinery caught fire in 2012, gas prices across the country shot up, but Hernandez saw that the health impacts were concentrated among his neighbors, “black and brown people who were filling up the hospitals, getting sick and having respiratory problems. That was the moment where I started to make the connection to environmental discrimination.” That issue now drives his work as an environmental justice organizer for COPAL MN, a Minneapolis organization focused on uniting Minnesota’s Latinx community through grassroots democracy.

Anticipating the ways that communities will have to cope with climate-related impacts and emergencies has also become a growing focus for cities. Kira Liu ’17 contributed to this effort when, while a student in Roopali Phadke’s class, she worked on a NOAA-funded project with the City of St. Paul called “Ready & Resilient,” showing residents how to look out for one another in the face of possible climate emergencies like flash floods, icier winter roads, and more mosquitoes. Learning how communities will have to come together to cope with climate-related problems is what now inspires her work as community engagement coordinator at Climate Generation, the organization founded by Arctic explorer Will Steger, which focuses on collective action to combat climate change. “It’s no longer enough to act individually, because it’s going to take all of us, standing together, to develop climate solutions and create a more equitable society,” she says.

Seeing how much energy and enthusiasm Liu and other Mac alums are bringing to the climate crisis is one way that Christie Manning manages her own climate anxiety. “What I see is that Macalester is giving students resources and tools to practice their skills, be more effective in their activism, and to raise their voices in really important ways.”

Although there are days when it’s distressing to talk to her classes about what will happen if the earth warms another degree, Manning says, the critical thinking they’re bringing to the climate emergency is cause for hope. “There are also these moments of silence where they sit back and absorb and say, ‘Okay, I understand what we’re facing here psychologically. I understand what we’re facing as a species.’ And then they lean forward and ask, ‘What’s the path forward? Can we talk more about solutions?’ Those are the questions you really want your students to be asking.”

Three Ways to Avoid Climate Burnout

Photo by Kelly MacGregor

GET OUTDOORS: As a glacier scientist, geology professor Kelly MacGregor has lost track of how many times she’s heard people say, “You’d better study those glaciers now, before they disappear.” Though comments like that can be depressing, MacGregor says that taking students to glaciers to conduct research is motivating. “It actually makes you feel empowered to understand the science of climate,” she says. Connecting with nature and finding a source of personal meaning in the natural world can also inspire conservation-minded behavior long after you’ve returned home.

CONCENTRATE ON THE BIG PICTURE: If you’ve been concerned about how humans are contributing to climate change, chances are you’re already carrying a reusable water bottle and trying to take the bus. While individual choices like flying less do make a difference, “This problem is bigger than any of us,” says Margaret Breen ’20. To expand the impact of your own environmentally sustainable choices, look for ways to support nonprofits and grassroots groups that are committed to a cleaner economy and climate justice—you may even know the Macalester alums who work for them.

IMAGINE THE FUTURE YOU WANT TO SEE: “When our bodies are quivering with anxiety, it doesn’t feel good and it doesn’t make us very effective at our work,” says Jason Rodney ’10, a youth program coordinator at Climate Generation. When Rodney meets with high school climate activists, “We start with storytelling, and we work together to visualize what a healed world would look like.” Instead of feeling overwhelmed by the weight of climate change, “we’re laughing together, we’re singing, and we’re really feeling hopeful about the future.”

By Laura Billings Coleman

Laura Billings Coleman is a freelance writer and frequent Macalester Today contributor.

January 21 2020

Back to top