Each winter, Macalester’s seniors gather in Kagin Commons for “Beer with Brian,” a chance to celebrate the start of their final semester and clink glasses with President Brian Rosenberg after he shares a few words of wisdom.

This year, Rosenberg told them, he felt keen empathy for seniors fielding all the questions about what’s next—especially when there’s no answer yet. Nearly a year after announcing that he’ll leave Macalester on May 31, 2020, his only plan so far was that he and his wife, Carol, were about to sign a lease on a Minneapolis apartment, as he later told The Mac Weekly. Beyond that, Rosenberg didn’t know what the next chapter might look like. Believe in your ability to navigate uncertainty, he told the seniors.

In that last semester of college, plans often unfold quickly and in unexpected ways. A few weeks later, Harvard University staff invited Rosenberg to spend the fall in Cambridge as the president-in-residence in the Harvard Graduate School of Education’s higher education program. The opportunity was a great fit.

“The one thing everyone tells me is that I’ve got to take a break, and they’re right, but I also can’t imagine sitting around for a year doing nothing,” says Rosenberg, who will instead attend classes alongside students, anchor academic discussions with real-world experience, and meet with students one-on-one and in groups. “This feels like a nice balance to me: I’ll be able to work directly with students, but I won’t have the same kinds of responsibilities I do now. It also gives me the opportunity to help shape future leaders in higher education.”

Rosenberg came to Macalester in 2003 from Lawrence University, where he was dean of the faculty and an English professor. A Charles Dickens scholar, he has written two books on the Victorian author as well as Creative Tensions: Civility, Empathy, and the Future of Liberal Education, a compilation of essays and speeches from his Macalester tenure.

Over the past 17 years, his leadership has shaped the college in both key ways and countless ways. The student body’s demographics have shifted significantly, especially among the college’s U.S. students who identify as students of color, which increased from 12 percent in 2003 to 28 percent in 2019. Rosenberg led the five-year, $156 million Step Forward campaign as well as the $125 million Macalester Moment campaign that the college will wrap up at the end of May. He has written prolifically on issues including higher education access and quality, tuition costs, and college rankings, as well as public policy.

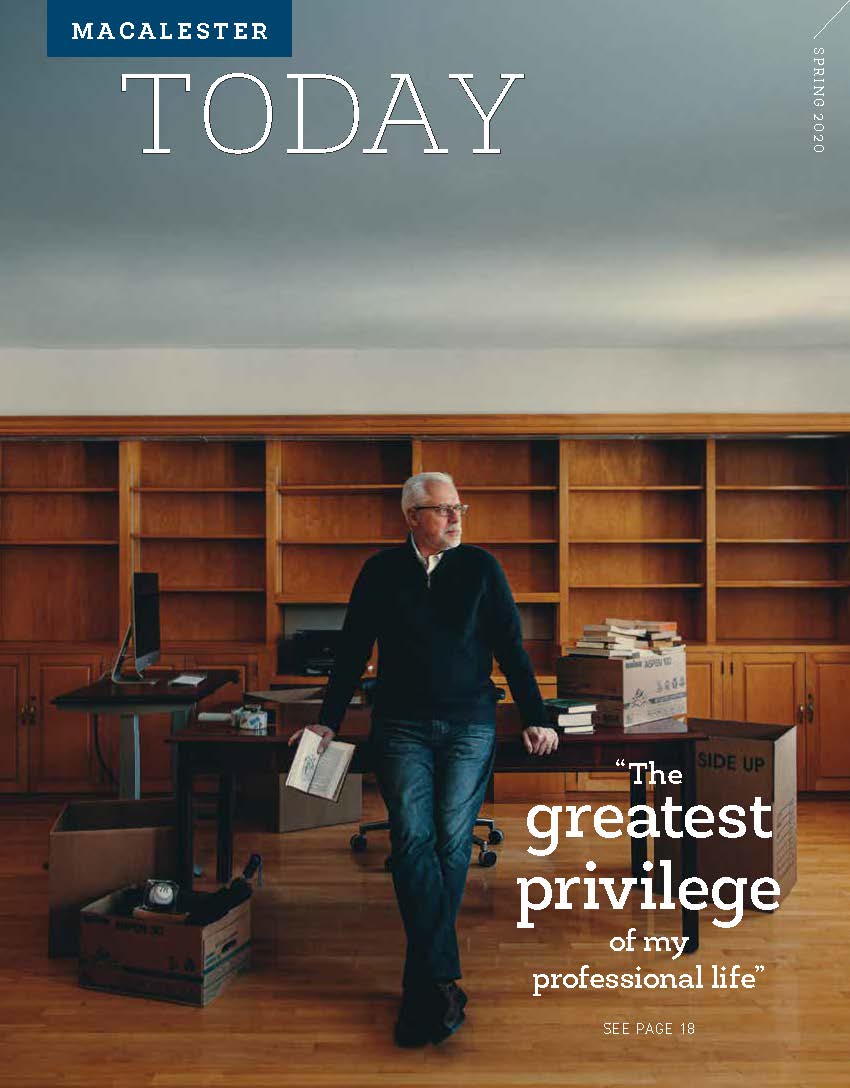

“The opportunity to serve as president of Macalester has been by far the greatest privilege of my professional life,” Rosenberg wrote in an April 2019 message to the community announcing his departure. “The longer I have stayed, the more impressed I have been by the excellence of our faculty, the dedication of the staff with whom I have worked side by side, and especially the passionate determination of our students and alumni to create a more just and peaceful world.”

In the past two years, Rosenberg conducted nearly 40 Big Questions interviews with students, alumni, faculty, and staff. Now it’s his turn to answer some big questions.

People have been asking for your advice on leadership a lot this year. What’s the first rule?

You’ve got to be authentic. So many presidents, because of all the pressures they’re under, forget that. Yes, you’re a public figure and you’re defined by your role, but be a human being. Listen to people. People have to have some trust that you’re going to speak to them honestly.

And then what?

When I talk to college presidents or people who might want to be college presidents, I want to make sure they understand that being a leader in an academic setting is very different from being a leader in most other settings, because you’re not in a position to tell very many people exactly what to do. Don’t expect to come in and give orders. It doesn’t work that way. You have to lead through example, inspiration, and political skill. If you want people on campus to behave a certain way, you have to set that example yourself. You have to have the skill and the evidence to persuade people. And sometimes you win arguments by not arguing—that’s a lesson I’ve had to work on over my whole career.

What do you remember from your first few weeks on campus?

I remember feeling kind of overwhelmed. I did feel prepared for the job, but everything in your life gets upended at the same time. I was worried about starting a new job, but then also about where my young kids were going to go to school. At the time, my wife, Carol, had temporarily stopped practicing medicine, and I wondered how she’d do with that. I tend to be a worrier.

What surprised you about being a college president?

I don’t think you can really prepare yourself for just how visible you are all the time as a college president. I knew intellectually that would be the case, but it still caught me by surprise. Every time you walk into a room, you’re the center of attention. People are always watching—not in a creepy or negative way, but they’re just noticing what you do. What’s your facial expression when you’re walking across campus? Are you smiling? You have to be attuned to the fact that every moment for you is a public moment.

A few years in, you began to be more outspoken about your views on public policy. How did that happen, and do you wish it would have happened sooner?

From the beginning, I wanted to have an authentic voice, but I certainly didn’t feel comfortable right away with having what could be described as a more controversial voice around public issues. That’s completely natural for a new president. You’re trying to learn your constituency, you’re trying to get the Board of Trustees comfortable with you—honestly, you just don’t want to lose your job.

As I settled into the presidency, I felt more open talking about matters of public policy. Around the same time, the world around us changed. A lot more happened, particularly in the past four or five years, that I felt touched directly on Macalester’s mission. Many presidents will say the same thing: you stay out of public issues. You stay out of divisive issues until and unless they touch upon your institution’s mission, and then you have an obligation to speak the truth. It’s my responsibility as the president to defend the mission of the college even when the issues are controversial.

During your tenure, Macalester’s demographics shifted significantly. How did that change happen?

Virtually from the moment I got here, students of color told me that a) there aren’t enough of us here and b) our experiences here aren’t good enough.

One person or office can’t change a college’s composition: lots of people have to prioritize it. First, we made sure that becoming a more diverse institution was an admissions priority. If I could point to one institutional decision that had the most impact, it’s probably joining the QuestBridge program, a college and scholarship application process that helps outstanding low-income high school seniors gain admission and full four-year scholarships to selective colleges.

Then the whole Student Affairs division, including the Department of Multicultural Life, works hard to make sure that students have a good experience here. That helps current students encourage prospective students of color to enroll. The importance of that piece cannot be overstated. If prospective students visit a college and current students tell them not to enroll there, they’re going to listen. The only way they’re going to enroll is if students who are already there say, “This is a place where you want to be. We want you here, and you can succeed here.”

In the last two years, we’ve brought in the most diverse groups of students in the college’s history. That’s no accident.

What else have students advocated for over the years that will stay with you?

The first group of activists that blew me away advocated for changing our policies for admitting undocumented students. At the time, undocumented applicants were part of the very large international applicant pool, and students argued that they should be treated as part of the domestic pool for both admissions and financial aid.

What was so impressive was that they didn’t just come in and say, “Here’s our list of demands.” They came in and talked to me, to Student Affairs, to Admissions, and they said, “What challenges do we need to overcome to make this happen?” They worked diligently and patiently, and they viewed the work as not so much protesting or challenging, but collaborating with campus partners to achieve an outcome. We ended up with not just more undocumented students, but undocumented students who had a better experience. I’ve always held up those activists as a model.

The Fossil Free Mac students, over multiple generations of students, were another really positive model. They were strategic, tenacious, respectful, practical, and realistic in their goals. They didn’t get everything they wanted, but they got a significant amount. I’ll never forget the sit-in outside the October 2019 board meeting. It was silent. Students were there for most of the day, doing homework. They weren’t disruptive, but they were really present, and that profoundly impressed the Board of Trustees. That sit-in will be something I’ll always remember.

How else has the community changed?

When I got here in 2003, I feel like there was a lot more negativity about Macalester. I think that today there’s a greater understanding among students, faculty, and staff of the importance and the excellence of Macalester’s work. That doesn’t mean that we’re not still a very self-critical community. We are. But [vice president for Student Affairs] Donna Lee likes to say that the criticism comes from a place of love, and I think she’s right: students love this place, so they push for it to be better. We’re certainly still on a journey, but we’re a stronger community now.

You’ve advocated for improving the Macalester experience for first-generation college students. How did that priority emerge?

By observing and talking to students, I’ve gained over time a deeper understanding of just how different going to school at a place like this is for someone who is the first member of their family to attend college, particularly if you come from a family that has been struggling with all of the inequities built into our society. It’s just a wholly different experience.

My wife, Carol, is a first-generation college student who came from a working class family. We met during freshman orientation at Cornell. My family was middle class, and my mother didn’t go to college, but my father did. Very few people in Carol’s extended family went to college, and if they did, they stayed close to home. Carol went six hours away from home.

That was so much more of a challenge for her than it was for me, and as an 18-year-old, I just didn’t get it. I don’t feel like I ever fully understood why her college experience was so different from mine—why she felt so much pressure to succeed and so much more guilt if, say, she got a B on an exam. That formative part of my life with her resonates very powerfully with me when I see what Macalester students are going through, and seeing what Macalester students experience has helped me understand my own history with Carol. I’m quite grateful for that.

Your two sons went through their own college searches during your presidency. What did you learn from that process?

Visiting campuses with them gave me a sense of how important it is when you talk to prospective students to be very clear about how your institution is different from others. So much of what we heard from colleges was the same, and you could just see 17-year-olds tune it out: “Here we go again about pizza with faculty members.”

I was also struck by how welcoming institutions were or weren’t. There were colleges we visited where it almost seemed like they were doing you a favor by letting you be there. And then there were other institutions that felt very welcoming, and it wasn’t always tied directly to status. Whenever I speak at events like spring samplers for admitted students, I always say, “Thank you for your interest in Macalester, and know that we appreciate it.” That’s not something colleges say all the time.

It was also fun because they had spent so much time with me that they were able pretty easily to see through the bullshit. They were a little bit more jaded than a typical 17-year-old consumer, just because they grew up here, listening to me jabber on for so many years.

You’ve said that college campuses are an intense reflection of the society around them. What do you see on campus this year?

The most intense issues on college campuses are the same issues that are most intense in our society, except college campuses are in some ways more concentrated versions because you have thousands of young people in an enclosed space. The issues that seem top of mind to me among students are issues of sexual assault and harassment, race and equity, and climate change. Out of all of the inexcusable things about my generation, the failure to wrestle with climate change is probably the worst. The level of awareness and anxiety about climate change among students now is much higher than it used to be.

There’s also the broader issue of mental health. In society, the level of anxiety and depression is epidemic and far beyond the ability of our health care system to manage and treat. That’s reflected on college campuses, where levels of anxiety and depression are extraordinarily high. I’ve yet to talk to a college president who feels like their institution is equipped fully to deal with that.

What’s the most important development in higher ed that you’ve seen in 17 years?

Among at least a lot of schools, there’s an increased awareness that they need to do something to work against our system’s embedded inequities. That just didn’t seem to be top of mind in higher ed 20 years ago. Although higher education can’t fix the K-12 system or housing or health care and everything else that creates inequities in our society, we’re doing a lot more now to make our campuses more diverse.

What’s the greatest challenge facing higher education?

The single biggest threat is cost. We’re just too expensive. For my entire career, I’ve heard speculation that people would stop paying the comprehensive fee once it hit $30,000, then $40,000, then $50,000. And for the most part, people kept coming. Now we’re going to cross $70,000. Within a decade, there will be colleges that cost $100,000 per year.

We’re nearing a breaking point. There’s an inability to figure out how to control costs and stop that relentless march upward, with the cost rising at a faster rate than revenue. It’s an unsustainable model. And that’s the most disappointing thing: that we haven’t figured out ways to bend that cost curve yet.

What would you do if you started a college from scratch?

One thing I’d do is not divide the college into 35 different departments. That model is expensive. It’s structurally complicated. It makes decision-making harder. And I’m not convinced that it provides students with the best education. The world that they’re going to move into isn’t divided into departments.

I really like the model that Fred Swaniker ’99 has developed in his African Leadership University. There, students don’t come in and pick a major—they define a problem they want to solve, and then they organize their studies around that problem. The Yale-National University of Singapore College, which was started in 2011, has done something similar.

At Macalester, it’s really exciting to see programs emerge such as Human Rights and Humanitarianism; Community and Global Health; and Food, Agriculture, and Society. Higher education needs to move more in that direction.

What role will you play in the transition to Macalester’s next president, Dr. Suzanne Rivera?

I want to be available as a resource but not to intrude myself in any way. That’s exactly the way Mike McPherson was when I came, and I found that really reassuring. It’ll be up to her. I’ll always be at the other end of a phone call or email, but I’m going to get out of the way.

In your first Macalester Today interview, you talked about the Dickens themes that guided you as you got started. Is there a different story on your mind 17 years later?

The lesson I’ve always tried to take away from Dickens is this: don’t lose your humanity when you become part of a structure. You always have to remember that even though there are rules and policies, sometimes you just have to be a human being. I’ve occasionally frustrated some people around here when I say, “I know we have that rule, but break it, because I want to do something for this person.” I’ve tried to carry that lesson from Dickens throughout all of my time here.

Dickens writes a lot about separations and partings—how they’re both painful and sad but also bring new beginnings. Many of his early novels have beaming, unrealistic happy endings. His later novels don’t. Most of them end on a bittersweet tone, with a mix of sadness and joy and hope and fear.

That’s very much what it feels like when you go through a major shift in your life. I’m thinking a lot, right now, about those endings.

“Brian told the Board of Trustees that he didn’t want Macalester to simply be one of the best colleges in the country—he wanted Macalester to be the best-managed college in the country. There’s been a lot of turmoil in the financial state of many colleges over Brian’s tenure, and Macalester has managed to emerge not just unscathed but in a very strong position. That’s clearly a function of leadership.” –Jeff Larson ’79 P’10

“Brian worked to encourage greater engagement with the Twin Cities. He provided course development funds for faculty to create urban engagement in the curriculum. Today more than 60 classes include a community-based learning component, and that’s in large part because of his long-term vision.” –Karine Moe, provost

“I vividly remember PBR saying in an interview that the single most important characteristic of an educated person is empathy: being able to see the world through the eyes of someone other than yourself. That idea became central to the education I was hoping to get at Macalester—cultivating a sense of wonder and depth of inquiry in engaging in the world and with those who inhabit it. I’m guided by that ethic that PBR instilled in me about the need to foster a more empathetic world.” –Forest Redlin ’16

“During my senior year, when I became the college’s first student liaison to the Board of Trustees, Brian took hours out of his busy schedule to mentor and empower me to create connections among trustees and students. He always remembered that educating students was the core purpose of Macalester. In the years since I graduated from Mac, I’ve tried to apply Brian’s best attributes to my own life: his work ethic; his ability to focus on the person in front of him, regardless of the many other things on his plate; the care with which he speaks and writes; and his willingness to stand against injustice, even when it is unconventional for someone in his role to do so.” –Blythe Austin ’08

“When Brian asked if I would paint the official portrait that will be displayed with the other presidents’ portraits in Weyerhaeuser, I felt really honored and also a responsibility to get it right. I have a lot of respect for him—he has shown great leadership and kindness. In the portrait, I wanted to bring out the part of Brian that people don’t always see: that he’s really funny. In part, he has to present this formal quality as a president, but you see his humor and lightness in places like the 2010 President’s Day video. In one scene, he was in my studio on the model stand, just hamming it up. I wanted to bring that sense of humor and warmth to the portrait and make it colorful and friendly and real.” –Chris Willcox, art professor

“I’ve learned as much about humanity from Brian as I have about how to do the work. Brian’s legacy will be both about his excellence as a leader and his reasoned, steady voice, but also someone who cares about humans, on a grand scale and on an individual level.” –Andrew Brown, vice president for Advancement

“Brian recharged the college’s commitment to internationalism through his vision for the Institute for Global Citizenship, a site for the confluence of high intellectual performance and the imperatives of civic life. He was instrumental in strengthening the study abroad experience for students. He understood deeply the importance of having international students represented on campus. When he arrived, we had 80 countries represented among our students. Today we have 98. That requires an intellectual and financial commitment—the college had to go out of its way to sustain that support, let alone expand it.” –Ahmed Samatar, international studies professor

“I worked on the Committee for Refugee Student Access, started by a classmate who wanted Macalester to recruit one or two students who are refugees or otherwise displaced. We met with PBR, and he talked to us about how things happen through the administration—what parts he could do and what parts needed to go through Admissions or other offices. Then he’d connect us with those people for those meetings. I can’t emphasize enough how much it meant that PBR was willing to meet and share ideas with us. It showed us that we could help make Macalester a better place for everyone.” –Muath Ibaid ’17

By Rebecca DeJarlais Ortiz ’06 / Photo by David J. Turner

April 22 2020

Back to top