The COVID-19 pandemic changed daily life, quickly and drastically. At work, we traded long commutes and in-person interaction with colleagues for extended hours in hastily set up home offices, concerns about job security, and upended work/life balance. As Macalester alumni changed gears, many leaned on skills they developed in college: flexibility, compassion, and willingness to serve and to learn. Read on to learn how some of our alumni navigated pandemic pivots—and how they’re thinking about what lies ahead.

Zachary Jordan ’20

CEO, easy-EMDR.com

With the COVID-19 pandemic fast-tracking digital transformations, tech-savvy Zachary Jordan has seen huge growth in demand for easy-EMDR, his digital trauma therapy tool that has helped psychotherapists treat their patients remotely during quarantine. “Easy-EMDR filled the telehealth need for therapy, offering inexpensive, all-in-one treatments in one site,” he says.

With the COVID-19 pandemic fast-tracking digital transformations, tech-savvy Zachary Jordan has seen huge growth in demand for easy-EMDR, his digital trauma therapy tool that has helped psychotherapists treat their patients remotely during quarantine. “Easy-EMDR filled the telehealth need for therapy, offering inexpensive, all-in-one treatments in one site,” he says.

Jordan launched easy-EMDR.com as a first-year student in 2016 after undergoing eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, a therapy that uses bilateral stimulus to help people heal after traumatic life experiences. “EMDR is very helpful,” Jordan says, “but it requires expensive physical equipment to complete. I started looking for a way to digitize it.”

He built a simple digital application that gained traction after exposure on Reddit led both therapists and their clients to the site. After receiving requests for more features, Jordan turned to Macalester’s entrepreneurship and innovation office for help, using a grant from Mac’s Live It Fund and support from the MacStartups incubator program to rebuild the site and make it telehealth compatible. Round two was launched in August 2019, and in March 2020, when the pandemic shut down in-person therapy sessions, Jordan’s tool hit its stride.

“It just exploded with everyone looking for options to continue EMDR remotely,” he says. Easy-EMDR currently subscribes approximately 5,000 therapists, with hundreds of thousands of visitors to the site, which allows therapists to conduct visual bilateral stimulation and connect with their clients in video sessions.

Jordan sees easy-EMDR eventually fitting into a suite of telehealth tools. “Telehealth is here to stay, especially given that we could see multiple recurrences of this virus or another one,” he says. “We will need to build comprehensive telehealth tools.”

The key to such tools is accessibility, Jordan says. He offers easy-EMDR for free to those who can’t afford a subscription and utilizes user feedback for updates. Ten percent of easy-EMDR’s profit goes to GiveDirectly’s international Universal Basic Income program, which helps people hardest hit by the COVID-19 crisis. “I want to set a good example and pressure other companies to be more charitable,” he says.

Marcia Zimmerman ’81

Senior rabbi, Temple Israel

As one of the largest reform synagogues in the country, Temple Israel was already exploring ways to use the internet to stay connected to its members when the pandemic hit. The ban on large gatherings in houses of worship just accelerated the pace of that virtual reality, says Marcia Zimmerman, who has been senior rabbi at Temple Israel in Minneapolis since 2001.

“We were already on the edges of a virtual presence,” she says. “COVID-19 has just made us very comfortable being online to create spiritual support for our congregants.” Last July, the temple hired a junior rabbi to help with online programming, and so was well prepared to meet the challenges of engaging the faithful without being able to gather in person.

For example, Temple Israel recently took 250 households on a virtual visit to Beit Hatfutsot, the Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv—many more people than would have been able to go on a physical trip. Congregants have performed and recorded music for use in live Shabbat services, and clergy members host an Instagram Live service each evening. The temple also has continued remote operation of its early childhood center and Hebrew school. “It’s really important to be with our congregants where they are and when they need us,” Zimmerman says.

The “very old program of Judaism” has been helpful in keeping the faithful engaged and connected during the pandemic, she says.

“We’ve really had to flex our muscles—perhaps those that have atrophied—in Jewish tradition and ritual, because that is what is going to hold us during this time,” she says, noting that families’ at-home participation in the prayers and rituals can only strengthen faith. “I hope we don’t lose that when we’re allowed to gather together again.”

Zimmerman and senior clergy of other faiths in downtown Minneapolis regularly gather to work together in promoting understanding and social justice, and that work has continued on Zoom during the pandemic. They’ve created an online interfaith service and continue to operate Align, a nonprofit that assists the homeless.

“Macalester taught me how to be active in making this world better,” Zimmerman says. “The act of Judaism for me is to leverage religion for good. Religious voices need to stand up and be truly powerful in changing the difficult and bad to better and good.”

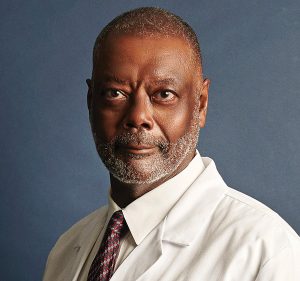

Stanley M. Berry ’75

High-risk obstetrician, Wayne State University

The pandemic created challenging dilemmas for many, including medical care providers. In March, high-risk obstetrician Stanley M. Berry faced the prospect of one of those unexpected crossroads: continue on his path into retirement or add his name to the list of doctors volunteering to join critical care in Detroit. In early April, he spoke with TIME magazine’s Jamie Ducharme about how he reached his decision to submit his name. Though Berry hasn’t gotten the call, he continues working for the National Institutes of Health at Wayne State University and volunteering at a high-risk obstetrics clinic. In this narrative—published April 9, 2020, and reprinted with permission—he reflects on facing this decision.

“I was planning to retire and finish my novel in the next year or two. I’m essentially an obstetrician who specializes in high-risk pregnancy. I only work three days a week right now, and one of those days is for research and mentoring.

“I was planning to retire and finish my novel in the next year or two. I’m essentially an obstetrician who specializes in high-risk pregnancy. I only work three days a week right now, and one of those days is for research and mentoring.

But Michigan needed to ‘repurpose’ some physicians who were willing to volunteer to treat COVID-19 patients. I submitted my name. I haven’t been assigned yet, but if they tell me they need people in the emergency room, that’s where I’ll go. I still know how to listen to lungs and take a medical history and do a physical, so I can contribute there. I don’t know how this is going to play out, because I’m almost 67.

A number of my friends have called to try to discourage me from volunteering, because of my age. One of my buds was really harsh. My rejoinder was, ‘What if your wife had to go to the hospital? You’d want someone to take care of her. Somebody has to do it.’ There were some tears shed by my fiancée, but she expressed an understanding of where I’m coming from. One might say there’s an element of selfishness in all this, because I do have three children, one of whom is severely disabled; I have a former wife who is a saint; I have a granddaughter who lives with my ex and we’re expecting another granddaughter. So I have family ties.

I never imagined a time like this, and I didn’t take this decision lightly. One physician friend of mine just got over her fever of four days, yesterday. One of my former residents is intubated because of coronavirus. And one of the anesthesiologists in the hospital is now transferred to the University of Michigan on ECMO. It’s on my mind, but I try not to think about it.

This could be the last thing I do on earth, but I felt very strongly about it. I go back to an interview I heard with an army officer who survived the Battle of Mogadishu in the 1990s. He said one of his men came to him and this guy said, ‘I’m afraid.’ He said back, ‘It’s not a matter of whether you have fear or not; it’s what you do with it.’ I do have fear.

But the bravest people that I knew of in my lifetime—Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr.—all knew they were going to die. They went ahead and did it anyway. I don’t want to die, and I’m not in this to be a hero, but medicine’s been good to me and the city of Detroit’s been good to me, and we’re being clobbered right now. My will is made, so I’m just going to try to follow all the guidelines for wearing personal protective equipment and help.”

Mercedes Burns ’06

Assistant professor of biological sciences; University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Mercedes Burns was teaching an advanced course called the “Evolution of Sex” when the University of Maryland, Baltimore County sent students home. She quickly learned the ins and outs of Blackboard Collaborate, an online teaching platform supported by UMBC, in order to move the class online.

Mercedes Burns was teaching an advanced course called the “Evolution of Sex” when the University of Maryland, Baltimore County sent students home. She quickly learned the ins and outs of Blackboard Collaborate, an online teaching platform supported by UMBC, in order to move the class online.

“It was my first time teaching this course and I had an idea of how it would go, which of course didn’t happen,” Burns says. Nonetheless, she was surprised by how easily students embraced technology, thriving and collaborating in everything from course meetings to small group chats to online presentations.

Perhaps even more challenging for Burns was figuring out how she could continue her research without regular access to laboratory facilities. She studies the genomic evolution of Opiliones—also known as daddy longlegs—and how some species reproduce both sexually and asexually.

When the university closed down, Burns and her postdoctoral fellow loaded up lab equipment to use at home. Her colleague conducts long-range DNA sequencing in her spare bedroom, keeps a centrifuge in the fridge, and stores reagents and samples in a deep freezer. Burns is dissecting preserved specimens—that she stores wedged between leftovers and bulk food in her freezer—with a microscope at her kitchen table.

“Having things in my life that I can control, like accessing my lab equipment at home so I can keep working on projects, has kept me grounded in a situation that feels pretty touch and go,” she says.

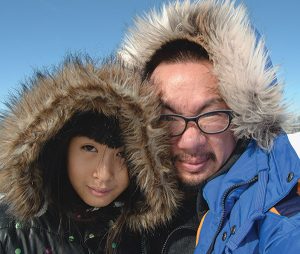

Bao Phi ’97

Poet and Loft Literary Center program director

Bao Phi ’97 is an award-winning Minneapolis poet and the author of four books, most recently the children’s picture book My Footprints (2019). He’s also a single co-parent of 10-year-old daughter Sông. In May, he spoke with MinnPost writer Pamela Espeland. Their conversation is excerpted and edited with permission.

What did your year look like before everything closed down?

I have my job at the Loft as full-time program director. I also do speaking engagements. Everything from going to a grade school to read picture books to little kids, to reading poetry and giving a workshop at a university or in another state. It’s the gig economy, basically. As a single parent, it’s what I have to do.

For some reason, before COVID hit, most of my bread-and-butter gigging happened from January through early March. I was actually grumpy about it, because every other week I was in my car or going to the airport. But I got very lucky this year.

What is your life like now?

When my daughter is with me, my life is very much a routine of three meals a day and making sure she’s up on her offsite learning.

I log into work. I try to get us outside once a day. We live by Powderhorn Park and do socially distanced free time until right before bed, when we watch one episode of “Adventure Time” together. Then we brush up and watch a funny short YouTube video, and then I get her to bed. Once she falls asleep, if I’m not too tired, I’ll either do some chores or watch TV or read something before I go to bed.

Work has been very busy. The Loft’s Wordplay festival had to pivot online. Wordplay is not my primary responsibility, but it’s all hands on deck. My life at the Loft has been helping out where I can and trying to learn very quickly this online stuff that all of us will probably have increasing responsibility for over the next year or so.

I’ve been doing live events for 20 years and can do that with one hand tied behind my back. But setting up and broadcasting a literary reading in a way that looks professional and is consistent with the values and branding of the organization is new territory for all of us.

You once said you wrote a poem a day. Do you still do that?

No, but I actually maintained that for a surprisingly long time. The caveat being that doesn’t mean it was a good poem.

I’ve been working on a novel off and on for the last 10 years. It’s basically an alternate history of the United States, where in the late ’90s there’s a virus that happens that turns people into zombies and Southeast Asians get blamed for it. I finally finished it a few months ago. I don’t know if it’s timely now or too soon. This is my first long-form anything. It could be terrible, but at least it’s done.

It seems that poets can respond immediately to anything. Is the pandemic making its way into your work?

That’s why I was drawn to poetry as a teenager. It’s why I became a poet. All of these things were happening—the first Persian Gulf War, police brutality—that required an immediate response. I felt compelled to comment and make sense of things through art. I couldn’t sing, I couldn’t rap, I couldn’t play any instruments. I tried theater—that’s a whole other thing!—but poetry was immediate. You could go to a rally, a coffee shop, or a meeting of friends in a basement with a poem, and no one could stop you.

The shelter-in-place has been very up and down for me. [At first] it was very difficult to write anything because I was so full of anxiety and anger. I don’t have to reiterate the huge number [of acts] of anti-Asian violence.

I want to be very clear here: Anti-Asian violence and discrimination are nothing new. Ever since I had consciousness, I have known that my race has made me an enemy. This is not new to me at all. But the whole heightenedness of it—the fact that it was almost justified at all levels of our civic life, not only super-blatant but also seemingly signed off on as being okay—was really damaging to me. It felt like the hate was cranked up to 11.

This was on top of the stress of working from home, being responsible for my daughter, not knowing if I’m going to have a job, and trying to help my elderly refugee parents, who are poor, negotiate all of this. It’s on top of what everyone else is also worried about. This anvil of anti-Asian racism.

It was just too much. So I didn’t write about it for a long time. Now I’ve written a little, but the writing is relatively new because the feelings are still very raw.

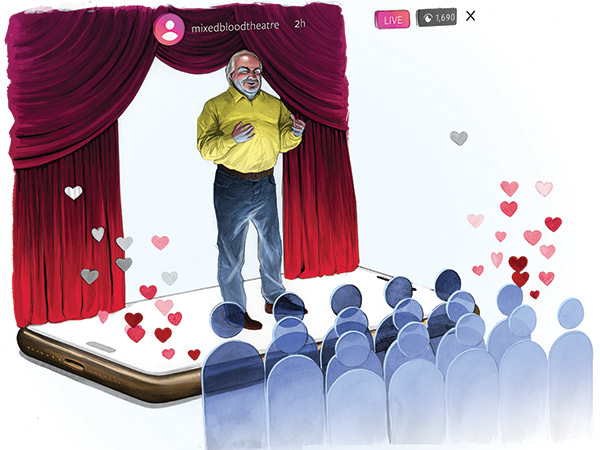

Jack Reuler ’75

Artistic Director, Mixed Blood Theatre

The new musical Interstate was in the middle of its run at the Mixed Blood Theatre when the production was shuttered amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The 45-year-old theater located in Minneapolis’s Cedar-Riverside neighborhood was founded by Jack Reuler during the summer after his graduation from Macalester, and this is the first time it’s closed its doors to audiences.

“Everything just slowed to nothing,” Reuler says, referencing not only Mixed Blood’s in-house theatrical productions, but its educational and outreach programs focused on social justice issues.

Even so, Mixed Blood is carrying on, using the time to reimagine what might be possible. “This shutdown is the great disruption that will allow us to reinvent ourselves,” Reuler says.

Because it relies on grants and donations for income rather than ticket revenue, Mixed Blood is in the unique position to be able to balance its budget, even with a curtailed season, Reuler says. The theater also received a small grant to hire several artists to create online content and maintains an active social media presence related to both theater and activism.

Reuler’s biggest challenge is figuring out what Mixed Blood’s new delivery system will look like, including what protocols need to be in place for artists, staff, and audiences to feel comfortable. Mixed Blood’s auditorium only seats 200, so Reuler and his staff are exploring the idea of leasing a larger venue to mount a production later this year. “That’ll allow us to have our traditional audience size of 200, but appropriately spaced among 1,000 seats,” he says.

As part of a collective brain trust among those who work in live entertainment—be it music, sports, or theater—Mixed Blood is leading the conversation on how to reopen doors to the public. “Because we don’t have the financial implications of missing ticket sales goals, we’re likely to be the canary in the coal mine. We’re still planning to produce a live event in 2020, where other theaters have delayed until later in 2021. Instead of waiting for a green light, Mixed Blood is moving forward, waiting for a red light and hoping it doesn’t come.”

Kate Agnew ’11

Senior manager, UnitedHealth Group

Like many of those who work in business, Kate Agnew, senior manager of platform engineering at Optum for UnitedHealth Group (UHG), found herself suddenly working from home when Minnesota’s stay-at-home orders went into effect mid-March.

Like many of those who work in business, Kate Agnew, senior manager of platform engineering at Optum for UnitedHealth Group (UHG), found herself suddenly working from home when Minnesota’s stay-at-home orders went into effect mid-March.

“My team of 14 engineers helps stand up platforms that facilitate the movement of data across the company and keep UnitedHealth Group running,” she says. The team already had processes and tools in place for flexibility, including working from home most Fridays, so the technical transition was fairly seamless. A larger challenge, says Agnew, proved to be combating a sense of disconnectedness among her team members.

“As manager, I’ve focused on how we can still feel like a team while we’re not sharing a physical space,” she says. Agnew got creative by organizing team lunches, coffees, and happy hours, offering optional daily 15-minute meetings or “water cooler time,” and encouraging participation in a broader-teamwide trivia contest. She values her own weekly happy hour with her peer group to share best practices for managing the company’s work-from-home teams.

Building such camaraderie helped Agnew’s team take on one of its pandemic-related projects, as UHG was contracted by the United States Department of Health and Human Services to administer a program that provides claims-based reimbursement to health care providers who conduct COVID-19 testing or provide treatment for uninsured individuals.

“Our team worked a lot of late hours to leverage the tools we already had in place to enable the platform capabilities to accelerate payments to providers through the crisis and simplify people’s access to care,” she says.

Agnew says this time at home has been a good reminder to be intentional about building community in the workplace. “I now see the value in connection,” she says. “When you’re faced with a tough situation like this pandemic, it’s important to have strong relationships to lean on.” To that end, she’s working to ensure that the two 2020 Macalester grads she has hired to join her team will have a good onboarding experience, despite the need to begin work remotely.

Toni Symonds ’83

Chief consultant; the California Assembly Committee on Jobs, Economic Development, and the Economy

Toni Symonds has spent 35 years in the California State Legislature, working on various policy committees for community and economic development. In her current role, Symonds analyzes, designs, and implements public policy initiatives in the areas of small business, finance, workforce development, trade, and state contracting.

Toni Symonds has spent 35 years in the California State Legislature, working on various policy committees for community and economic development. In her current role, Symonds analyzes, designs, and implements public policy initiatives in the areas of small business, finance, workforce development, trade, and state contracting.

When the pandemic began, Symonds’s first challenge was telecommuting, which previously had been against legislature policy. Faced with a pressing need to stay in touch with her stakeholders and a strong desire to support small businesses through disruptive change, she turned to online communication: sending thrice-weekly summaries of COVID-19 news and available resources that distill vast amounts of information into a sort of one-stop shop for stakeholders.

“My primary mission is to make sure everyone is up to date,” says Symonds, who also developed a website that includes resources to assist small businesses, entrepreneurs, workers, and economic and workforce development professionals in responding to COVID-19 challenges. “The ability to observe, sort, re-sort, and observe from a different perspective without judgment—skills I learned at Macalester—has been extremely valuable to me in what I do.”

Throughout California’s stay-at-home orders, Symonds, who recently conducted her first paperless hearing, has noticed a shift in the legislature’s approach to telecommuting. As the committee looks at the future of work, Symonds hopes some changes will remain. “We’re realizing people can adapt, while being flexible, efficient, and productive,” she says.

By Marla Holt / Illustrations by Obadah Aljefri

Marla Holt is a freelance writer based in Owatonna, Minn.

August 18 2020

Back to top