He went by Bobo: a jokester prone to pranks and charmed by life in the Mississippi Delta—the countryside, extended family, and the stately homes of Greenwood. In the photographs that would immortalize him, you see semblances of a baby face: wide eyes, chubby cheeks, and a kind smile. The brutal violence he’d experience belies what we all know but rarely confront: Emmett Till was a kid. And he was killed for doing what kids do—testing the bounds of what’s considered appropriate.

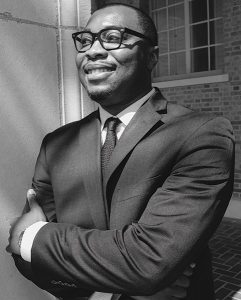

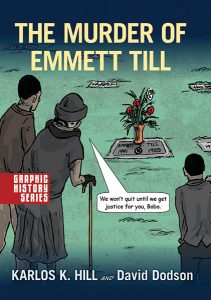

These are among the things we come to terms with in The Murder of Emmett Till, a graphic novel by Karlos K. Hill ’02, historian and Black studies professor at the University of Oklahoma. It tells the story of Till, who at the age of 14 was killed in 1955 after allegedly whistling at a white woman. For years, Hill has focused his scholarship and activism on understanding America’s history of racial violence.

It’s a calling he felt while at Macalester. “I became a historian because of three professors: James Stewart’s lectures were some of the most interesting and energetic I’ve ever witnessed. When I think of great teaching, I think of him. Mahmoud El-Kati helped me understand the importance of African American history and social justice. And Peter Rachleff is the reason I got into graduate school,” Hill says. “I would not be where I am without those three. They still shape me today.”

Hill developed his focus on racial violence in graduate school, which stemmed, in part, from the visual. “I began doing archival research and became bowled over by the stories of lynching, the photographs of lynching, and just became intrigued with this aspect of American history that, for the most part, there’s very little public consciousness around. I just remember being so emotionally disturbed and distraught doing the research.”

Hill developed his focus on racial violence in graduate school, which stemmed, in part, from the visual. “I began doing archival research and became bowled over by the stories of lynching, the photographs of lynching, and just became intrigued with this aspect of American history that, for the most part, there’s very little public consciousness around. I just remember being so emotionally disturbed and distraught doing the research.”

Given this background, Hill treats the subject of lynching with both delicacy and rigor. He did the work, and it shows. Hill’s first book, Beyond the Rope: The Impact of Lynching on Black Culture and Memory, explores a concept he calls the lynched Black body. It’s a way of understanding how representations of lynched Black people were used to achieve social and political ends—like advocating for anti-lynching laws. “Till’s case is an example of the lynched Black body and how it got deployed,” he says.

And yet, The Murder of Emmett Till is different from most academic treatments of lynching. Much of that difference is the medium itself. Depicting such a brutal attack in the form of a graphic novel is a tall order, but one Hill was committed to getting right: “I could have just referenced lynching in the text, but graphic history is about telling the story with images in a way that if you remove the text, people can still understand what’s happening.”

Part of that depiction was breathing life into a person who history remembers as a victim. Hill worked hard to jettison that tendency: Chief among the decisions he made was to use Till’s nickname—Bobo—granting him the very thing he’d be deprived of, a childhood filled with curiosity and mistakes.

In the panels, we see a boy who loved the big city but relished aspects of country life, even at his own peril. At one point in the novel, Till shoots firecrackers in public, to the chagrin of his Southern relatives. I held my breath, knowing the price he could pay for causing a ruckus. Even though I know how Till’s story ends, I cared for Bobo, and didn’t want this to be the thing that cost him his life. Mistakes are pricey in the Jim Crow south, even for kids.

Implicit in Hill reconstructing Till’s life is an understanding that history is as much a series of facts as it is actions. People did things—and so part of the challenge is imagining how to honor what the historical record doesn’t always depict: “When I’m creating this narrative, I’m acting it out. I’m in my office imagining conversations between [Till’s mother] Mamie and Bobo based on the historical record, saying the words that are written down in the narrative.”

Till’s horrific murder presented another challenge: “We know that [Till] was subjected to a terrible beating, but we don’t actually know what happened, so I wanted to be restrained there for those reasons. We imagined this book being read in high school and college classes. I wanted those particular audiences to understand that he was beaten, but I didn’t want to sensationalize the violence.”

Which brings us to the Till tragedy’s central paradox: His body was never meant to be seen, in large part because the country had moved on from the public spectacles lynchings once were, according to Hill: “Southerners understood that the system of segregation is vulnerable to attack. And they understood that wanton acts of violence, public spectacles only bring undue attention to this system and make it more vulnerable.”

To that end, Till’s terribly bludgeoned body had become a weapon of sorts. In the novel, we see Mamie come to terms with his murder and her eventual indignation, which led to the devastating and radical decision to open her son’s casket, exposing the disfigurement. Look at what they did.

“Mamie Till’s decision to let the world see what they did to her boy was not just a courageous act. It turned on its head the ways in which photographs of lynched or murdered Black bodies had been used previously,” Hill says. “What Mamie did was say, ‘Okay, I’m going to take something that you want to be secret and make that public.’”

The parallels between this book and the current moment aren’t lost on Hill. This summer was also all about the visual: the most urgent filmmaking being done was by people with smartphones, witnessing things that were once kept hidden. Acts of violence compelling us to look at ourselves.

The parallels between this book and the current moment aren’t lost on Hill. This summer was also all about the visual: the most urgent filmmaking being done was by people with smartphones, witnessing things that were once kept hidden. Acts of violence compelling us to look at ourselves.

The visual—and what it can do to people—is still top of mind for Hill, whose courses often include units on lynching. He’s concerned with how young people, especially students of color, might consume these images, so he offers a teaching guide in the novel on how to talk with young people about lynching.

But even Hill is still learning. When we spoke, there was an urgency in his voice when discussing what it means to teach racial violence today. “Students can feel anguish when seeing lynchings or brutality against Black bodies. They can shut down intellectually if they’re not given a chance to process what they’re feeling,” he says. “That needs to be at the forefront of the class. And so when I teach the history of lynching again, I won’t teach it the same. It’s going to be completely different for those reasons.”

The utility of these lessons is more important than ever, Hill suggests, especially given the spate of Black people killed in recent years. Where there is a potential for trauma, there’s also potential for care. And that has to matter, too. It won’t be easy, but looking away isn’t an option.

By Tinbete Ermyas ’08 / Illustration by David Dodson / Photo by Jackie Manz

Tinbete Ermyas ’08 is an editor at National Public Radio in Washington, D.C.

October 21 2020

Back to top