By Matthew Dewald / Photo illustrations by Charles Jischke

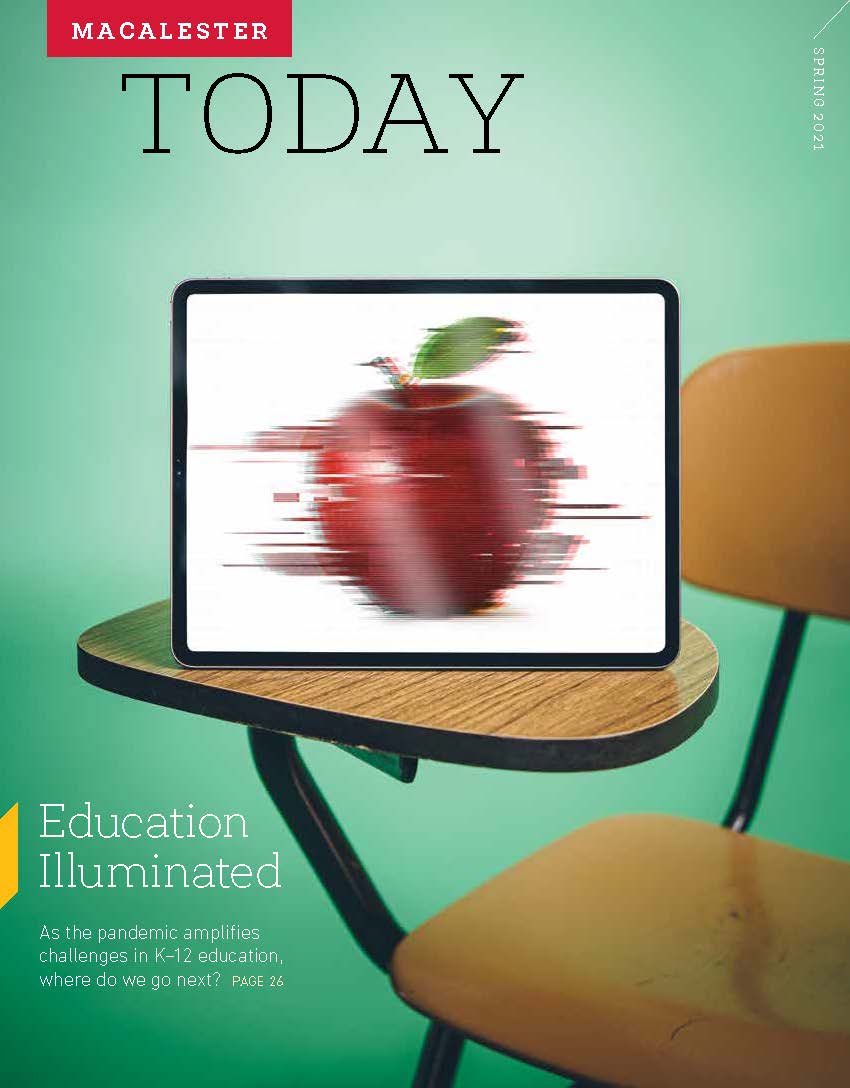

Among all professionals, K–12 educators have faced some of the biggest pandemic-prompted challenges in their work. The abrupt shutdowns and shift to remote learning upended the most fundamental aspects of their jobs. As the pandemic continued to rage, teachers and administrators were caught in the crossfire of public debates about whether and how to reopen schools. Politicians, school boards, and parents created often conflicting pressures, even as educators themselves weighed the difficult balance between anxieties about their own health and safety and the very real needs of their students.

Still, each weekday morning, these educators continue to put on game faces and conjure classrooms for students. Whether the setting is virtual, in-person, or some kind of hybrid, teachers are doing their best to mitigate the significant academic, social, and psychological losses of the last year. Many of the issues they are dealing with are not new, at least to them. The pandemic has shined a harsh light on the flaws of the educational system. Many teachers and administrators hope it will also illuminate a way forward.

Here, we talk to education experts about their experiences over the past year with the vulnerabilities in public education—and how we can improve it in the future.

Brian Lozenski says that education may not be the great equalizer we once believed.

When schools closed in March 2020, virtual learning exacerbated inequalities that in-person learning had helped mitigate and, to some extent, mask. Some students had computers and internet access at home, while others had no way to participate in virtual classes. Children who relied on school for subsidized breakfast and lunch were going hungry. Kids whose parents were essential workers were home alone, sometimes watching younger siblings while they did their own schoolwork. Meanwhile, students from better-resourced families could log on to their classes with ease—or even learn in a “pod” with a private tutor the parents had hired.

These aspects of the pandemic made blindingly apparent something that Brian Lozenski, an associate professor of urban and multicultural education at Macalester, had already observed: The resources families have going into school are the best predictor of what a school will do for them. This new awareness is prompting new questions about education’s effectiveness as an equalizer in American society.

“The pandemic has really jolted people into a different sense of reality,” he says.

When the pandemic hit, the social and cultural fabric of the classroom space was ripped away. “What that showed us was that the cultural context of school is fundamental to any educational project,” he says. “Absent that, just relying on a skills-based, almost technical approach to education is really lacking.”

Lozenski hopes the pandemic has opened room for curricular revisions that emphasize interdisciplinary, social learning focused on asking big questions about how people relate to one another, whether politically, economically, or socially. He believes that not positioning students as “citizens-in-waiting” and instead treating them as fully engaged participants in society can better increase student motivation and achievement and better prepare them for the world they will enter.

“What I’m hoping to see as we come out of this is more questioning about how we want to live together,” Lozenski says. “We’re seeing some clear indications that our society is not functioning. A lot of communities have been naming this for decades, saying things aren’t working very well for us. I think you’re starting to see more and more people recognize that.”

Beatrice Rendon plans to continue to use technology tools that appeal to more learning styles.

Beatrice Rendon ’13, a second-grade teacher at Waite Park Community School in Minneapolis, started the 2020-21 school year with a challenge: Getting a Google Meet link to 30 seven-year-olds.

After that came talking them through downloading apps, building relationships with them, and coaching well-meaning parents who might not know how the technology worked either. Sometimes the home helpers were older siblings left home and in charge by working parents and themselves trying to keep up with their own virtual learning. There were internet glitches, sound issues, and more as she and her students climbed the learning curve.

“It’s kind of a blur thinking back to the first six or eight weeks,” she says. “I just remember keeping everything super positive, and the kids being so amazing and patient.”

Out of those struggles came new insights into how she can use these technology tools to better reach all learners. For example, she has begun prerecording instructions for activities and adding visual icons to guide students. This allows students who are not yet proficient readers to engage independently with the activities. The technology platform Rendon uses also increases her ability to offer differentiated instruction tailored to students’ strengths and needs.

As she develops these and other adaptations under challenging circumstances, she hopes that a greater recognition of teachers’ professionalism will be another outcome of the pandemic.

“My biggest wish for post-pandemic teaching and learning is that it’s more humane,” she says. “I think everybody needs to take a deep breath and trust the education professionals. In a normal year, I’m teaching kids who are reading and doing math from a pre-K to a middle school level. Teaching kids who are behind is not new to any of us, but we’ll do it best if we’re supported and trusted.”

Addy Kessler wants to encourage more curiosity and true learning.

Addy Kessler ’04 is already living in a world many teachers can only dream about. She teaches product design at Lincoln High School in downtown Portland, Oregon, and has such strong support from her administration that her principal once asked her what her dream class would be and then approved the proposal she developed.

This support and the flexibility she inherently has as an arts educator play a key role in her satisfaction. While arts education has national standards, it hasn’t been saddled with detailed state mandates about content or the high-stakes standardized testing that teachers in other subject areas have—which can allow for more meaningful conversations and growth.

For example, instead of tests, she has students create portfolios. She grades students on the demonstration of technical and conceptual understanding, not on the quality and quantity of works. She engages in regular conversations about the work in progress, areas of improvement, and where they are finding success.

The approach encourages learning through a process of experimentation, self-analysis, and self-critique. Experimentation—“where the magic happens,” she says—is rewarded, even if it doesn’t work out the way the teacher or student had planned. While she says she hears the phrase “learning loss” a lot these days, she thinks that’s not quite the right focus. “Students are learning. We don’t need to be forcing our usual expectations on to students during an unusual time,” she says.

Kessler says she’s learned a lot about supporting the social and emotional needs of her students during this past year, and the value of creating community. “I’ve had to change things up and learn how to connect with people in different ways—it has been challenging but also really great,” she says. “I think this will forever impact the way I approach my teaching going forward.”

Jesse Hagopian wants us to ditch high-stakes testing once and for all.

Jesse Hagopian ’01, who teaches history and ethnic studies at Garfield High School in Seattle, has long been a critic of high-stakes standardized testing, such as state-level achievement tests and college entrance exams. Among the things he says the tests do not measure are students’ wisdom, problem-solving abilities, critical thinking skills, empathy, ability to work with other people, or intellect.

The current pandemic, he says, has brought the shortcomings of high-stakes testing into relief. Evidence of this is the federal government’s decision to waive requirements for standardized testing in the spring of 2020, when students of all backgrounds faced significant stresses. He contrasts this with a normal year when the unique stresses facing students from disadvantaged backgrounds are overlooked. Now that more people understand the relationship between life stress and testing, what should change?

“I think we need to invest the money in authentic forms of assessment,” he says.

He cites the example of New York Performance Standards Consortium, a group of 38 public schools that are exempt from state standardized testing requirements. Instead, students complete long-term, in-depth projects tailored to their interests. Student learning is evaluated through teacher-developed performance assessments specific to the curriculum, rather than imposed top-down through multiple-choice questions developed by a state testing board.

Hagopian likens the process to the interaction of a doctoral student and dissertation adviser. “I think that’s a model for transforming assessment that really meets the needs of our kids,” he says.

Data backs him up. A 2020 report by researchers at the City University of New York found that although Consortium students began high school “more educationally and economically disadvantaged than their peers,” they were more likely than their peers to graduate high school, attend college, and succeed there.

Leyla Suleiman thinks it’s time to diversify the voices that influence decisions.

Language arts teacher Leyla Suleiman ’17 was teaching at Park Center Senior High School in Brooklyn Park, Minnesota, when, like the rest of her colleagues, she shifted to distance education in March 2020. Her experience as her district developed plans for returning to in-person learning has shown her the critical importance of broadening the voices that influence decision-making at the district level.

This fall, she will be required to return to the classroom. The idea elates her, but it also makes her nervous because she doesn’t yet know what the prevailing public health conditions will be then. She is also concerned for the teens Park Center serves, many of whom come from populations disproportionately affected by the pandemic. It has high numbers of students who receive free and reduced lunches, who come from non-English-speaking households, and who are students of color. Students who often don’t, in other words, have much of a safety net.

As her district began making decisions about returning to some in-school instruction at the beginning of the 2020-21 school year, “things got pretty messy,” she says. Some teachers took to the streets for public protests against a return to in-person learning, Suleiman among them.

“Of course, I want to go back,” she says. “That’s literally the phrase that I put on the sign that I was holding up at that protest: ‘I want to teach safely.’ I want to be with my students as soon as possible, but I want to protect my family, and I also want to protect my students.”

She believes that increasing effective, intentional outreach efforts to disadvantaged communities would strengthen district-wide decision-making. Without it, she worries that the voices of her students and their families are not sufficiently heard on this and other questions.

Lesley Lavery wants to make the teaching profession more diverse and more appealing to young professionals.

Before the pandemic struck, 17 percent of new teachers were leaving the profession within the first five years, according to a report from the National Center for Education Statistics. Lesley Lavery, an associate professor of political science at Macalester, won’t be surprised if that figure rises when data reflecting the pandemic era comes in.

Two-thirds of teachers leave the profession for reasons other than retirement, according to a 2017 report by the Learning Policy Institute. It cited lack of administrative support and dissatisfaction with working conditions among the top reasons for their departure. Both of these issues contribute to a dynamic that Lavery has seen during the pandemic. The federal government pushed decisions about school reopening to the governors. The governors then pushed the decisions down to local districts. Local districts sat back while teacher unions publicly voiced nuts-and-bolts concerns about a safe return to in-person learning. Teachers then took the blame if schools didn’t reopen.

“It’s often the case that it is the superintendent or a school board that is not ready to go back, but they don’t come out and say it,” Lavery says.

She worries that this kind of mixed messaging, plus concerns about pay levels, will make it particularly difficult to recruit teachers of color, which the profession desperately needs more of. In 2012, they made up just 18 percent of the public school teacher workforce, even as students of color made up 49 percent of all public school students.

“That’s not the type of work that is going to attract the diverse Black and brown students that make it through college,” she says. “They want a job that’s rewarding, and they want a job that pays well enough.”

Jumaane Saunders says we should rethink basic structures of the school day and year.

Jumaane Saunders ’00, until recently a principal in Brooklyn Prospect Charter School in New York City, says the pandemic highlighted the education system’s rigid reliance on outdated structures.

“We do school the exact same way we did it in the late 1800s and early 1900s: the schoolroom with students at desks and a teacher in the front,” he says. But when classes went remote last year because they had to, parents and kids realized some time-honored educational traditions weren’t necessary.

Similarly, he points to the school calendar, a holdover from an agrarian economy. “Kids have summer break for picking season, but how many kids are tending the fields now in America? Yet we

still follow that same model even though we know as educators that two months off leads to a loss of educational knowledge, what we call the summer brain drain.”

These days, students are learning asynchronously, and parents are finding alternative online academies and even forming small clusters to hire teachers themselves.

“I’ve heard stories of that happening all over the country, from people who have a lot of money to impoverished communities,” he says. “I think there needs to be a serious conversation in this country about what K–12 education needs to look like going forward.”

Matthew Dewald is a writer in Richmond, Virginia.

April 23 2021

Back to top