By Joe Linstroth / Illustration by Adolfo Valle

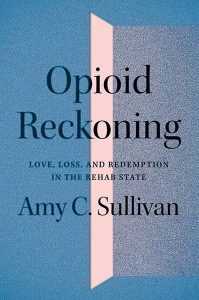

Minnesota’s alcohol and drug rehabilitation programs have long been held up as the gold-standard. For generations, the so-called “Minnesota Model” has served as the predominant approach around the world to treating people with addictions. But when it comes to addressing the opioid crisis, visiting history professor Dr. Amy Sullivan argues in her new book Opioid Reckoning: Love, Loss, and Redemption in the Rehab State (University of Minnesota Press) that the Minnesota Model has fallen short, and the sluggish shift to a more effective one has cost our society dearly. Weaving in her own family’s story with the accounts of current and former opioid users, parents, doctors and treatment providers, Professor Sullivan aims a spotlight at the stories of ordinary people who are struggling with and working to end the opioid crisis that has ravaged communities across the state and country.

Minnesota’s alcohol and drug rehabilitation programs have long been held up as the gold-standard. For generations, the so-called “Minnesota Model” has served as the predominant approach around the world to treating people with addictions. But when it comes to addressing the opioid crisis, visiting history professor Dr. Amy Sullivan argues in her new book Opioid Reckoning: Love, Loss, and Redemption in the Rehab State (University of Minnesota Press) that the Minnesota Model has fallen short, and the sluggish shift to a more effective one has cost our society dearly. Weaving in her own family’s story with the accounts of current and former opioid users, parents, doctors and treatment providers, Professor Sullivan aims a spotlight at the stories of ordinary people who are struggling with and working to end the opioid crisis that has ravaged communities across the state and country.

Q: How did Minnesota end up being known as “The Rehab State”?

A: In the late 1930s and 40s, the Alcoholics Anonymous movement was in its beginning, and at the same time, there were people working within what were called mental asylums and psychiatric hospitals who wanted things to change for alcoholics in their care. They knew it wasn’t right that alcoholics were being locked up for life and that there was another way. AA came along and created a new model for that, one that was peer-driven and not institution-driven. This all coalesced in Minnesota: Willmar State Hospital staff were interested in doing something different. Hazelden, which was set up for doctors, priests, and professionals to find sobriety, wanted to do something innovative. And then Pioneer House—a residential home with a peer support network—all three of these organizations began basing their treatment models on the Twelve Steps of AA and abstinence.

Q: What is the Minnesota Model?

A: The Minnesota Model is based on the Twelve Steps and enhanced by professional social workers, therapists, and others, with the after care centered on peer recovery through AA meeting attendance. It’s based on treating people with alcoholism as “recoverable,” as whole people, providing all kinds of surround-care, including a spiritual life. The Minnesota Model was revolutionary because of its approach and flexibility. It treated alcoholism but also looked at underlying issues. And it was revolutionary—it ended institutionalization and provided a temporary but safe place to begin the recovery process.

Q: How does the Minnesota Model differ from what’s known now as the harm reduction model?

A: The harm reduction model is about “meeting people where they are at”—and that’s one of the key phrases, with an eye towards respecting individuals and promoting “any positive change.” It’s about reducing harm and building relationships so that the people who are using drugs will trust you and will feel respected and not seen just as someone who should be arrested, put in detox, or hauled off to treatment. It’s about treating people with dignity and respect. This model does not have its origins in treating alcoholism, it has its origins in injection drug use in the HIV era. And that is why this system developed completely separately from the Minnesota Model. The treatment model that we’re used to, the Minnesota Model, became entrenched in state government and insurance companies, but it was first only meant for people who had some way to pay their way out of their crisis—to then be in a safe place where they could get 24-hour care for 28 days. Harm reduction outreach workers had no such access to care and treatment for their clients. These two models developed completely separately.

Q: You note in the introduction that the push and pull between these two models is one of the key conflicts in the book. What’s the result of that conflict?

A: That people overdose and die unnecessarily. It’s the conflict in the book because it’s a historical conflict. What I hope that I revealed is how these two models—as well as increased access to the evidence-based medicines that help manage opioid use disorders—are starting to be integrated. Now you have Hazelden Betty Ford using phrases like “reducing harm.” Clients in abstinence-based centers might now leave treatment with Narcan and might even be on opioid agonist medications. This was a complete sea change for an abstinence-based organization that for decades only told people to go to AA or NA meetings after treatment.

Q: The first chapter focuses on mothers who are dealing with their children’s opioid addictions. What lessons did you take away from their experiences?

A: Well, first of all, I was in awe of their humility and gained great respect for their candor and sharing. My daughter is alive and thriving, even helping people in her work today who struggle on those margins. My friends who’ve lost children, their willingness to share their stories shows me that mothering is one of the most important things we have in our culture to sustain healthy communities. Mothers who lost their children to an opioid overdose are now turning their attention towards changing laws, knocking on legislators’ doors, speaking to the public, going to high schools—even their own child’s former school—to speak. That kind of courage and commitment is not about those mothers’ grief. It’s about the extent to which they care about other people’s children and the extent to which they don’t want other people to go through what they’ve gone through.

Q: As you write about in the book, the subject of opioid addiction is also very personal. You have a daughter who struggled and nearly died from her addiction. How did that experience affect your interactions with the people you interviewed for this book?

A: Well, I am so fortunate that she lived and that she is living a full, healthy, happy life today. Our family’s experience ended up being an incredibly powerful connector for me as a researcher because most of my narrators had similar experiences, from the same or different vantage points on the topic. This created a powerful space between us for trust, acceptance, and insights. I was ignorant about opioids and addiction ten years ago, and I learned an incredible amount from my beloved daughter and from all of my narrators, whether they are in the book or not.

Q: You write a lot about stigma—for families, for the doctors who treat people of addiction, for the users themselves. Regarding families, there’s a prevailing assumption in American society today that someone who becomes addicted to drugs must come from a dysfunctional family. How does that stigma play out for these families that you spoke with?

A: It’s really painful because all of a sudden you find yourself in situations that you could never have imagined with a child who could die at any moment. For privileged families—those with access to resources and with racial privileges—it comes as a horrible shock and devastation that they are ashamed of, and that they don’t want people in their families to know about. For people with fewer resources and no racial privilege, the common stereotypes and prejudices about drug use feeds on itself and makes those families also feel shame. For all families, social stigma and stereotyping of drug users makes what they’re already going through that much more difficult.

Q: There’s also a stigma around opioid users themselves, of course. How does race factor into how we look at the opioid epidemic?

A: Illicit drug use has always been highly racialized, and I have three brief answers to this huge question. First, one of the most effective medicines for opioid use disorder, methadone, has always been racialized. Heroin users and methadone clinics were stigmatized because media attention about heroin use centered on urban Black communities—and then methadone clinics in those places made the drug itself associated with those entrenched prejudices. These urban communities were mixed race, obviously, but African-American users were the ones who were stereotyped. That set in motion opposition to methadone as a treatment model and also stigmatized heroin users.

Racial injustice also factors into opioid deaths. In Minnesota, African-Americans overdose and die at twice the rate of Whites. Among tribal nations in Minnesota, it is seven times the number. Looking solely at the tribal nations in Minnesota and comparing their death rates to the rest of the country, it would register as a horrific crisis, but because we integrate that data and say, “Oh, look, it’s not that bad here in Minnesota,” that’s only because the number of white people in the population dilutes the problem. So, yes, racism is a huge part of the problem.

Finally, criminalization. The war on drugs has actually been a war on people, and disproportionately on people of color. The U.S. has incarcerated people with addiction by the millions for low-level drug offenses, and White people, for the most part, did not end up in prison to the degree that Black people did. Race has been embedded in substance use and criminalization in as sweeping a manner as it has been in every single aspect of our culture.

Q: You teach a class called “Uses and Abuses: Drug Addiction and Recovery,” which you’ve been teaching since 2016. What do your students find most eye-opening when they take that class?

A: I think the opportunity to talk about drug and substance use and alcohol has been clearly one of the most important things for many of these students. They feel patronized by the way that we treat college students as if they’re actually children, but they’re supposed to behave like adults. They’re right in that liminal space between childhood and adulthood, and when they don’t feel trusted that can lead to harmful consequences and harmful behaviors. Some of them say, “Why didn’t I have this in high school? It would have kept me out of so much trouble.” They learn things they’ve never had the opportunity to learn before, and they get to see something from a perspective that’s never been offered to them.

Q: In the book, you mention one story about a former student who applied what they learned in class in a very real way. Can you briefly recount that?

A: Since the second time I taught the class, I’ve included training on how to use Narcan, which is the opioid overdose antidote that brings a person literally back to life. Last year, even though we were online, I was determined that my students were still going to get Narcan training, so I mailed each of them kits or met students on campus to give them one. And then one day last November, one of my students wrote to me to tell me that they were able to save a guy on a bus that day because of the Narcan that I sent them. My student was elated. I think, for me, that experience made everything I do in the classroom, every interview I’ve had with people, all the work, it made it worth something.

Q: The book emerged out of the oral history project you created called The Minnesota Opioid Project. What is that project all about?

A: The project started well before I knew I was going to write a book. I wanted to make an oral history collection of as many people as I could interview as possible who were affected by the crisis—individuals, parents, doctors, care providers, and others. I had no intention of writing a book using those interviews until I was approached by the publisher. I’m still working on the interviews and I plan to eventually donate them to the University of Minnesota’s Social Welfare History Archive.

Q: What are your hopes for this project and this book?

A: I hope to bring the stories of ordinary people and people who are working to end the opioid epidemic to the forefront of our minds and conversations. I also hope to convey how this issue is experienced by people on all sides of the problem so that we can truly dismantle the stigma that comes with opioids and other drug use and start working deliberately and methodically to decriminalize drugs. An addiction shouldn’t destroy a life or a person’s future. I want readers to see how it has been and how we can do better.

October 22 2021

Back to top