By Hillary Moses Mohaupt ’08

For decades Macalester’s mission has emphasized a commitment to internationalism, multiculturalism, and service to society. Together, these values attract students who aren’t afraid to challenge the status quo. “Activism has always been a big part of what Macalester is all about,” says Jim Bennett ’69.

Students change during their time at Macalester, and they have, in turn, pushed Macalester to change, too. Over the years, issues that have captured the nation’s attention also have played out on campus, and students have urged Mac to use institutional power in service of justice. Students who have advocated for changes to the college’s policies have learned that making real, sustainable change is often a long game that requires commitment and stamina.

During their time at Mac, students have protested the Vietnam War, taken part in the Civil Rights Movement, and pressed for the recognition of the rights of immigrants and people across the gender spectrum. We asked six alumni across generations to reflect on their activism at Mac and how it has influenced their lives.

Expanding opportunities

When Jim Bennett ’69 arrived on campus in the fall of 1966 as a member of the varsity basketball team, there were just a handful of other Black students in his first-year class. He had graduated from an all-Black high school in Texas, and even now he remembers the culture shock. “Given the stark cultural change, if it had not been for basketball,” he says, “I probably would have gone home for Thanksgiving and never come back.”

When Jim Bennett ’69 arrived on campus in the fall of 1966 as a member of the varsity basketball team, there were just a handful of other Black students in his first-year class. He had graduated from an all-Black high school in Texas, and even now he remembers the culture shock. “Given the stark cultural change, if it had not been for basketball,” he says, “I probably would have gone home for Thanksgiving and never come back.”

“There were advantages to a Macalester education, but it was difficult for me to understand why, as a Black student, I had to give up who I was to be successful at Macalester. That was the motivation for talking with some other Black students and starting the Black Liberation Affairs Committee (BLAC).”

Black students were starting Black student unions at colleges across the country. “We wanted something to represent what we believed, as young people, was the right thing to do,” he remembers.

After the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, a collaborative group of students, including representatives from BLAC. student government, and others, met with President Arthur Flemming. Bennett says, “We asked the question, ‘Given what has happened with the assassination of Dr. King, and cities burning across the country, couldn’t and shouldn’t Macalester do more?’”

These conversations with the president resulted in the creation of the Expanded Educational Opportunities program, or EEO, which provided scholarships for full tuition and books. In the fall of 1969, it brought to campus seventy-five students of lower socioeconomic backgrounds, the majority of them Black.

The EEO was funded initially through the college’s endowment, and later through federal funding. Funding challenges eventually led to its demise in 1984, but over the course of its fifteen-year run the program helped diversify the racial makeup of the student body.

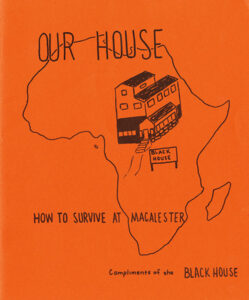

Bennett also led the college’s new Black Education and Cultural Center, or Black House, which also launched in 1969. Black House served as a hub of social and cultural activity, with a fully stocked third-floor library, community dinners, and African dance and drumming classes.

“I guess I didn’t really look at it as activism at that time,” Bennett says. “I would have perceived it as survival.”

After Macalester, Bennett earned a master’s in interdisciplinary studies at Mankato State University and a PhD in higher education administration at the University of Washington. He eventually served as vice president of equity and pluralism at Bellevue College, a public institution near Seattle.

“If the true meaning of education is to lead out of ignorance, then our responsibility is to not only understand the students who come to us,” he says, “but to try to learn from them in ways that we can be better stewards of the educational process.”

Bennett says founding BLAC and Black House and advocating for the EEO program laid a solid foundation for his future career. “I learned a lot about being an administrator in a higher-education setting. That’s where it started.”

Learning to negotiate

When Linda Kennedy ’72 was a student at Mac, student activism focused on the Vietnam War. But things changed for her, for her classmates, and for students across the country in late April 1970, when the nation learned that President Nixon had lied about American forces being in Cambodia.

When Linda Kennedy ’72 was a student at Mac, student activism focused on the Vietnam War. But things changed for her, for her classmates, and for students across the country in late April 1970, when the nation learned that President Nixon had lied about American forces being in Cambodia.

“There was sort of a groundswell,” she remembers now. “We felt we needed to make a statement that was bigger.”

As part of strikes happening across the country, Macalester students occupied Grand Avenue. “I was in the crowd, and it was thrilling and important and exciting and like breathing,” she says. “It was vital that we work to end this war and that we make others aware that we needed to stop it,” she says. “So we hauled a bench from a bus stop out into the street between Dupre and the dining commons. And then we shut the school down. We refused to go to class.”

The college closed for a week in early May. Because the semester was almost over, the college opted to give students grades of “incomplete.”

Students pushed back against the college’s grade policy and negotiated an alternative with professors: students would receive grades based on the work completed. Kennedy remembers that working with professors to give grades instead of incompletes was a turning point for her and her classmates. And for her male classmates, passing grades were no insignificant achievement, since good grades would help them avoid being drafted.

“It was the first time I negotiated something with an adult,” Kennedy says. “Growing up when I did, I was always taught to give great respect to adults.” She says the experience, with both parties displaying mutual respect, gave her confidence later as a broadcast journalist, when she was frequently the only Black woman in the newsroom.

Ultimately, joining the anti-war protests, then negotiating grades with the college gave Kennedy something more than a complete semester. “It’s not confidence; it’s not self-esteem,” she says. “It’s having that sense that you have power, too, that you can reply, you can respond, and get the desired result.”

Divesting from South Africa

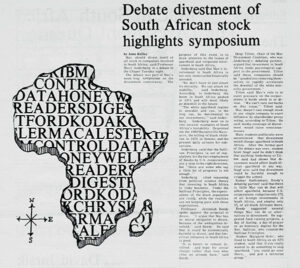

Macalester’s reputation as a center of activism against the Vietnam War attracted Doug Tilton ’82 to the college. But at the time he didn’t know anything about the growing international movement against apartheid in South Africa.

Macalester’s reputation as a center of activism against the Vietnam War attracted Doug Tilton ’82 to the college. But at the time he didn’t know anything about the growing international movement against apartheid in South Africa.

That changed one rainy night during his first year, when he was taking a break from working on a paper in Doty Hall. “I went down to the lounge to buy some candy and out of the rain comes this Norman Watkins ’79 saying, ‘Does anyone want to see a film about South Africa?’ That sounded more interesting than my paper.” Tilton followed Watkins over to the chapel basement, where the student group Macalester Anti-Apartheid Coalition (MAAC), was showing the film Last Grave at Dimbaza.

Afterward, Watkins issued a call to action: We’ve got to do something about this. Tilton, who describes himself then as “an activist looking for a cause” was in. Saying yes that night changed the course of his life.

Divestment involves withdrawing money invested in certain industries or funds to protest a particular policy. Since the early 1960s key political voices across the world had been calling for divestment from South Africa in protest of apartheid. College and universities, the National Council of Churches, and the NAACP, among other groups, joined in the divestment movement.

Macalester’s Board of Trustees formed a committee to look at the issue, and Tilton served as the student representative. Some members of the committee opposed divestment, on the grounds that Macalester had recently endured a rough financial patch. But Tilton remembers that MAAC had a lot of faculty support: “This was not a faculty movement, but there were a number of faculty members whose moral support and encouragement built our confidence and made us feel like what we were doing was important.”

Ultimately the committee and the trustees recommended limited divestment. As it turned out, Mac didn’t have many investments that were directly connected to South Africa. Tilton welcomed the outcome, but saw it as incomplete.

The Presbyterian Church, which played a role in the divestment campaign in the US, was also a significant force in Tilton’s life: his father was a minister, while his mother worked in the national offices. Tilton later interned in the Washington, D.C., offices of the Presbyterian Church (USA) focusing on anti-apartheid work there. He completed graduate work on South Africa. Today he lives in Paarl, South Africa, and works as regional liaison for Southern Africa for World Mission of the Presbyterian Church (USA).

Advocacy Today

Divestment continues to be a tactic for activists. In 2019, in response to student-led Fossil Free Mac’s divestment proposal and the college’s Social Responsibility Committee report, the college’s Board of Trustees divested of all dedicated publicly traded oil and gas assets, and adopted a college investment policy that prohibits new investments that are solely invested in oil and gas assets.

Including all genders

Bobbi Gass ’10 became co-chair of Queer Union (QU) during her sophomore year, and started working to create gender-neutral bathrooms on campus.

Bobbi Gass ’10 became co-chair of Queer Union (QU) during her sophomore year, and started working to create gender-neutral bathrooms on campus.

“The college was touted as a queer-friendly campus but we were quick to point out that it wasn’t so much for trans or nonbinary students,” she says.

Gass and other QU members met with campus administrators to advocate for gender-neutral locker rooms and restrooms in the new athletic center. Although the Leonard Center plans were already finalized, Gass says QU’s efforts led to other discussions about making life easier for trans and nonbinary students by designating some bathrooms in residence halls and in the basement of the Campus Center as gender neutral. Those conversations led, in turn, to a consideration of all-gender housing.

By Gass’s junior year, Mac’s first all-gender housing option opened in Kirk. “It was a pretty quick turnaround, now that I think about it,” she says. “But it felt like it was the direction the college needed to go.”

Since graduating, Gass has continued to fight for queer issues and trans people in the Twin Cities. She earned a master’s of public health from the University of Minnesota, and works in harm reduction for Hennepin County. The experience of working with college staff and fellow students at Mac gave Gass more confidence in her ability to transform the world around her, especially for the queer community. “It made me feel like my voice mattered and that it is possible to make change happen,” she says now.

Daring to DREAM

When Jocelyne Cardona ’14 joined ¡Adelante! as a first-year student in 2010, the on-campus cultural organization dedicated to creating awareness around Latin American identity, culture, and history, was focused on advocating for farmworkers and labor rights. Student activists engaged people by offering education, and “inviting them into the conversation, regardless of where they’re coming from,” she says.

When Jocelyne Cardona ’14 joined ¡Adelante! as a first-year student in 2010, the on-campus cultural organization dedicated to creating awareness around Latin American identity, culture, and history, was focused on advocating for farmworkers and labor rights. Student activists engaged people by offering education, and “inviting them into the conversation, regardless of where they’re coming from,” she says.

The following academic year ¡Adelante! took the same approach when it supported the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act, a federal legislative proposal to permanently protect people who came to the US as children. Originally introduced in 2001, at least eleven versions of the bill have been introduced in the last twenty years. Cardona says the group’s goal was to educate the college about why ensuring access to an education at Mac was so important. “We wanted the end of that campaign to be with the college itself adopting and endorsing the DREAM Act, and taking a political stance.”

In 2012, Congress passed the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, policy, which provides some temporary protections to some immigrants who came to the US as children. Cardona and a group of students created the Dare to DREAM Committee, separate from ¡Adelante!, to advocate for the college to support the DREAM Act. First-year student Adan Martinez ’16 joined them.

In 2012, Congress passed the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, policy, which provides some temporary protections to some immigrants who came to the US as children. Cardona and a group of students created the Dare to DREAM Committee, separate from ¡Adelante!, to advocate for the college to support the DREAM Act. First-year student Adan Martinez ’16 joined them.

One of the committee’s core missions was to change how Macalester offered funding to undocumented students. At the time, the Admissions Office processed applications from undocumented students as though they were international students—even if the students had lived in the US for practically their whole lives. Cardona says they focused on what was in Macalester’s control. “Admissions became our first system collaborator, so that was our first goal for the next couple of years—just actually creating avenues for access,” she says.

Because they weren’t legal permanent residents, undocumented students couldn’t receive federal financial aid—so while they could be accepted to Macalester, paying for a Mac education was a near-insurmountable hurdle. Under DACA, students could apply for state-based financial aid in some states. The Dare to DREAM committee asked Macalester to join colleges and universities across the country in endorsing the DREAM Act.

The group met with then-President Brian Rosenberg and shared their proposal for the college to publicly endorse the DREAM Act. They also collected signatures of support from students and faculty. As a result, Rosenberg and the Board of Trustees endorsed the DREAM Act in 2013. Today the Lealtad-Suzuki Center for Social Justice (formerly Department of Multicultural Life) supports DACA staff and students with services and resources for legal services and financial aid.

In addition to advocating for changes at Macalester, students in the Dare to DREAM committee worked with the state’s senators to help ensure that the Minnesota DREAM Act passed.

Martinez, who is earning a PhD in political science at the University of California–Berkeley, came to Mac having attended many protests and marches. He describes the experience of working with the Dare to DREAM committee as “activism from within.” He says, “In many ways, it incorporated a lot of what I was learning in my curriculum—how to create a good argument, how to articulate a good argument, and how to work with people in power.”

Cardona now works as a senior research associate at WestEd, a research, development, and service agency devoted to improving education and fostering an equitable society. “This work [at Macalester] gave me an example of what changing systems can look like, and that it is in fact possible,” she says. “Reflection itself is not enough. We all can do something with the privilege that we have.”

Hillary Moses Mohaupt ’08 earned a master’s degree in public history and is a freelance writer in the greater Philadelphia area.

April 28 2023

Back to top