By Julie Hessler ’85

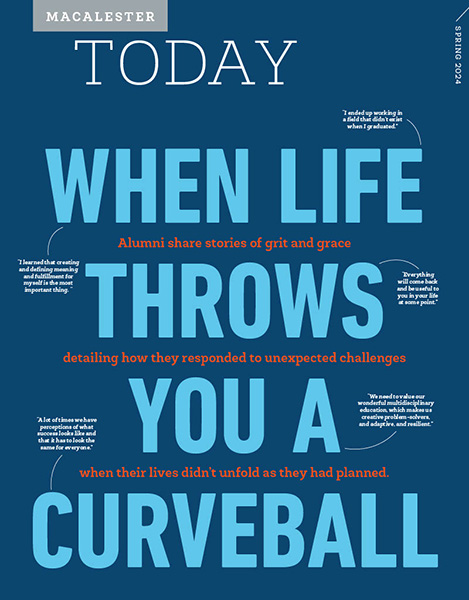

Last spring, Macalester Engagement hosted its first online Curveball conversation. Eight alumni, including Marie Deschamps ’04, who inspired the program, shared stories of life and careers post-Mac: the struggles they faced, including loss and mental health challenges, and the often surprising steps they took to make a more meaningful life.

Throughout, alumni leaned into their liberal arts degrees, critical thinking skills, and their own courage and resilience. Some found support from members of the Macalester community. In that spirit, we share edited excerpts of their stories for anyone in need of encouragement, wisdom, and inspiration.

Marie Deschamps ’04

Houston, Texas

When Marie Deschamps was at Macalester, she had a big plan. She was going to become an ob-gyn and work at Doctors Without Borders. She designed her academic experience around that, studying pre-med, political science, and gender studies and doing every clinical internship possible. There was, she says, no plan B.

When Marie Deschamps was at Macalester, she had a big plan. She was going to become an ob-gyn and work at Doctors Without Borders. She designed her academic experience around that, studying pre-med, political science, and gender studies and doing every clinical internship possible. There was, she says, no plan B.

But once she got to medical school, she was miserable. She made the really tough decision to leave. What followed was years of not feeling comfortable with her decision and an increasing toll on her emotional and psychological health. “I was living in the basement of my parents’ home, suffering from severe depression,” she says. “My mom, thinking she was going to do something good for me, said, ‘Look, the Macalester Today magazine arrived. Don’t you want to read it? It’s your lovely school that you love so much.’ And I remember I just cried and I said, ‘I cannot look at this magazine right now.’ And she said, ‘But why is that?’ ‘Because I cannot be reminded that everyone else is doing so well, and I’m the only one who is not.’”

Looking back, Deschamps says it wasn’t her reality, but it felt like it. Eventually, she reached out to her Macalester community, finding support from other alumni who were struggling and others who were willing to help, like Datra Oliver ’04 and Dev Oliver ’04, and Leonardo Barquero ’04. With their friendship and lots of art therapy, she built up her emotional resilience and in turn her life, a career, and a family. Today, she is an artist and art psychotherapist, a visiting scholar at New York’s New School, and finishing her PhD in expressive arts therapy. Her research, inspired in many ways by her mental-health journey, focuses on distress detection and technological art-based innovation.

But her earlier experience stayed with her. She decided to do something to make sure other alumni knew it was OK to reach out, that life happened, up and down and full of unexpected turns. “I went to campus and I told my story—my failure story, my human story,” she says. Her story was the genesis for Curveball, and her hope is that conversations like this bring self-care and well-being into the conversation when alumni plan for life post-Mac. As Deschamps puts it, “We need to value our wonderful multidisciplinary education, which makes us creative problem-solvers, and adaptive, and resilient. It is up to us to shift our academic narrative from individual success to collective wellness.”

Dion Cunningham ’06

Nassau, The Bahamas

Bahamians, says Dion Cunningham ’06, are taught at a very early age to do something that you can take back to your community. Cunningham says he was expected to choose a career path that was useful and could help some of the main industries of his country, such as tourism, banking and finance, law, or medicine.

Bahamians, says Dion Cunningham ’06, are taught at a very early age to do something that you can take back to your community. Cunningham says he was expected to choose a career path that was useful and could help some of the main industries of his country, such as tourism, banking and finance, law, or medicine.

Even though music had been a part of his life from an early age, he decided it would be a hobby, not a career. He studied biology, but halfway through his second year the piano player added a music degree. “Everyone at Mac was double or triple majoring, so I said, ‘Why not?’”

After graduation, Cunningham returned home to The Bahamas to take a year off before taking the MCATs and going to medical school. He landed a year-long position as a biology teacher in the public-school system. His first curveball was a phone call from the school. They couldn’t hire him as a science teacher after all. Would he consider teaching music instead? He wasn’t thrilled, but he accepted, and a one-year position turned into five years.

Cunningham continued to study and took the MCATs, but he wasn’t getting into his preferred schools. Even while he was teaching music he felt disappointed. “I had to use the science degree that my parents had paid for to do something that’s practical,” he says. He chose a new field—marine science—and earned his scuba certifications.

But doors were opening for him in music. He began accompanying local choral groups, and when the late opera singer Carmen Balthorp came to The Bahamas, she asked Cunningham to accompany her for a series of concerts. “Dion, why are you here on this island?” she asked him. Cunningham said, “I have a science degree, but I’m here as a music teacher and that’s the only door that’s opening for me right now.” She said, “No, you have to keep on studying.”

Inspired, Cunningham decided to seriously devote himself to the piano. “I could play, but I didn’t believe I had enough talent to pursue a performing career,” he says. “But I said, ‘I’m going to go for this.’”

Cunningham was later accepted into the Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University where he earned his master’s degree. He then earned a doctorate of music from the University of Maryland, College Park.

Now in his fourth year as an assistant professor at the University of The Bahamas, he says that curves sometimes turn into full circles. His dissertation wasn’t a performance CD. Rather, it’s about intersections of instrumental performance and human neuromechanics—a convergence of science and music. He continues to research the intersections of piano playing, injury prevention, and brain development.

He says, “In the words of many Bahamians, ‘I’m a testimony of the fact that nothing is ever wasted. That it will come back and be useful to you in your life at some point, even if not immediately.’”

Maya Benedict ’17

Minneapolis

Maya Benedict assumed that after graduation she’d take her degree in international studies, move to Washington, DC, and work for the State Department or the Foreign Service. “But when I graduated, it quickly became clear that despite all of my big plans, I couldn’t afford to move to DC,” she says. “My resume wasn’t very attractive because I couldn’t afford to do a lot of the unpaid internships that other students did. None of the places that I applied to work at ever responded.”

Maya Benedict assumed that after graduation she’d take her degree in international studies, move to Washington, DC, and work for the State Department or the Foreign Service. “But when I graduated, it quickly became clear that despite all of my big plans, I couldn’t afford to move to DC,” she says. “My resume wasn’t very attractive because I couldn’t afford to do a lot of the unpaid internships that other students did. None of the places that I applied to work at ever responded.”

Her first curveball was deciding to continue working as a butcher at the St. Paul Meat Shop, where she had worked as an undergrad. “For a while, I was frustrated that I was working in food service after graduating,” she says. “I felt like I wasn’t an ‘ideal’ Mac student, and even though I learned so much and really enjoyed my job, I felt like I wasn’t one of the alumni that Mac as an institution was proud of. I felt judged sometimes about being in food service, and I felt like I didn’t measure up to my friends and classmates.” Not knowing her future, she says, was scary and alienating.

But after four years and some solid reflection, Benedict realized she wanted to go to graduate school in public health. Even though she didn’t have experience in the field, she was admitted to the public health administration and policy program at the University of Minnesota. As a first-year she got a research job assessing food system employment issues in Minnesota’s meat processing industry, which covered her tuition.

That was her second curveball. “I never expected that I would continue to do some sort of meat work,” she says. “I got that job because of my food service experience. That was the unexpected moment that made my master’s degree possible.” Benedict says she’s still friends with her Meat Shop bosses and coworkers and proud of her work and what she learned. “I want to be very clear that I don’t consider myself ‘more successful’ because I left food service,” she says. Rather, the takeaway of her curveball story is that it was a defining period in her life and it opened up a whole different career path, she says. “I learned invaluable skills that I still use to this day.” Benedict is now a senior state program administrator at the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, where she administers statewide grant programs for food producers and meat processors.

“The work that I’m doing now to support local food systems is really fascinating to me,” she says. “I learned that creating and defining meaning and fulfillment for myself is the most important thing. That is going to change over time, and I should afford grace and understanding to myself and an openness to the unexpected.”

Hillary Drake ’03

Minneapolis

Two weeks after graduating into a recession, Hillary Drake didn’t know what she was going to do. A temp agency sent the political science major to a third-party logistics company that needed someone to file and answer the phones. Two weeks later, Drake was the customer success manager for their second-biggest customer. “I figured out that I love operations, I love the pace, I love the new problems every day,” she says. “Sometimes I don’t love what the problems are, but they’re always interesting things to solve.”

Two weeks after graduating into a recession, Hillary Drake didn’t know what she was going to do. A temp agency sent the political science major to a third-party logistics company that needed someone to file and answer the phones. Two weeks later, Drake was the customer success manager for their second-biggest customer. “I figured out that I love operations, I love the pace, I love the new problems every day,” she says. “Sometimes I don’t love what the problems are, but they’re always interesting things to solve.”

She finished her MBA in 2008, graduating into another recession. Over the past twenty years, she’s worked at seven or eight companies. Last spring, as this Curveball panel was being identified, Drake had quit her job, and was trying to figure out what she was going to do next.

Her partner encouraged her to explore the “entrepreneurial thing” that she’d been talking about for months. She reached out to fellow alum Josiah Carlson ’02 for coffee. Several months later, they launched a cloud services company called Liminal Network that makes it easy for businesses to implement APIs. Drake serves as co-founder and CEO.

“The real point is I’ve been on this huge journey,” says Drake. “Every time I thought I knew what I was getting into it was the wrong choice. Every time I have listened to the universe, I have been open to that possibility. I’ve grown through that and I ended up working in a field that didn’t exist when I graduated, working with technology that had barely been invented, and it’s a lot more fun now.”

One of the biggest lessons Drake says she has learned is how to let go, which can feel at odds with the high-achieving, perfect Macalester student ethos. “I can quit my job,” she says. “I don’t need to stay here and fix something they don’t want to fix. For me, learning that has been many years and a lot of therapy, and coming to that realization has helped me enormously. So I’m saying it out loud because sometimes you can kickstart things.”

And if you want to talk business careers one-on-one with Hillary, she’s happy to do so: “Hit me up on LinkedIn at Hillary Drake,” she says.

Danny Schwartzman ’04

Minneapolis

When Danny Schwartzman ’04 graduated he wanted to be part of creating something positive in the world. The political science major was doing political organizing work, and he worked on a series of political campaigns. But a few years in, he says, “I felt like I should do something that I really wanted to do.”

When Danny Schwartzman ’04 graduated he wanted to be part of creating something positive in the world. The political science major was doing political organizing work, and he worked on a series of political campaigns. But a few years in, he says, “I felt like I should do something that I really wanted to do.”

He wanted to start a restaurant, even though he didn’t know how and he didn’t have any experience. He leapt in anyway, meeting with about 100 people, many of whom he knew from Macalester networks and student organizing, and got their feedback on his plan.

His plan was ambitious: open a local restaurant that is welcoming; makes everything from scratch; offers a creative community space to meet; has high labor standards; sources its food with integrity and uses local farmers whenever possible; and rejects the standard food system that almost every other place seems to use.

A week before his restaurant, Common Roots Cafe, opened in south Minneapolis, Schwartzman experienced his first curveball. His general manager, whom he had hired to be in charge day to day while Schwartzman learned the ropes, was relocating. Schwartzman was on his own. “For the next fifteen years, I ran a restaurant without much professional experience,” he says, “and I quickly got it.”

More curveballs followed. Making money running a restaurant is hard. Running a restaurant the way Schwartzman wanted to—even though it felt like the right thing to do—was much harder. “I kept on pivoting,” he says. “I added levels of complexity, including a large catering business, and a second location to manage catering. We were doing up to five simultaneous weddings and had over 100 staff. It was extreme, and I realized that was the path to being significantly profitable.”

It also made running his business ridiculously complicated, he says. He reached a point where it was no longer manageable. The triple challenges of reemerging after the COVID-19 pandemic, dealing with a very difficult hiring climate for filling higher-level positions, and navigating a unionizing process made Schwartzman realize that it was all just too much.

He closed down the business he loved and is figuring out what’s next. He’ll tap the wide array of skills and large network he grew at Common Roots. “I know that I don’t want to run a restaurant,” he says. “I don’t actually know what the curveball leads to yet, but I feel good about it.”

Emily P.G. Erickson ’08

St. Paul

When Emily P.G. Erickson ’08 graduated with degrees in psychology and geography, she was jazzed about her honors project on the psychology of urban sustainability. Geography professor David Lanegran told her she should be an urban planner, and she listened. She eventually served as the City of St. Paul’s first sustainable transportation planner. Her work became central to her identity.

When Emily P.G. Erickson ’08 graduated with degrees in psychology and geography, she was jazzed about her honors project on the psychology of urban sustainability. Geography professor David Lanegran told her she should be an urban planner, and she listened. She eventually served as the City of St. Paul’s first sustainable transportation planner. Her work became central to her identity.

“I was one of those alumni that you see in the two-page spread of Macalester Today,” she recalls. “In summer 2012, at the same time I was featured in the magazine, curveball number one came my way via this growing sense of unease.”

Even though she knew that urban planning was important, her real passion was psychology. “I made the really hard choice to step away from the extrinsic motivators like promotions and press and take the leap to honor what drove me intrinsically,” she says. “It was thrilling and genuinely frightening.”

She left urban planning, intent on a doctoral degree in psychology. Once again, she worked hard and thrived professionally, landing a plum research job with the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

A month after she completed the master’s portion of her education, she gave birth to her first child with husband Lance Erickson ’04. After she returned from parental leave came her second curveball. Motherhood really put into perspective that the demands of continuing down the path to an academic career weren’t a fit with her family situation. Moreover, academia wasn’t the only place to pursue her passion for psychology.

When Erickson’s son was nine months old, she quit her research job to stay home with him. “People really do begin every conversation with ‘What do you do?’” she says. “And when you’re not comfortable with your answer or, in my case, didn’t have paid work to answer with, that was a hard space to be in.”

But Erickson says she also felt elated to be building a life closely aligned with her values and priorities. While caring full-time for her children (she now has three sons), she read, talked to people, tapped her network, took a lot of different classes, and found her way to writing. “And now, writing about mental health and parenting is work that I genuinely love,” she says. Her work has been published in the New York Times, American Psychological Association, Wired, Verywell Mind, Everyday Health, and other publications.

Erickson says she’s flexible about what’s to come in a way that she wasn’t when she began her working life. “I honestly feel less certain about exactly where I’ll be in ten years,” she says. “But at the same time I’m more confident I’ll be able to handle any more curveballs to come.”

Danica Surman ’14

Texas City, Texas

When Danica Surman was in college, she knew that politics was going to be her path. She recruited a classmate to run for state representative and ran their campaign as an independent study for her political science degree. In 2014, she was recruited to run for state representative. At the same time, she was running a political action committee targeting young voters and serving as party staff for the state Republican Party.

When Danica Surman was in college, she knew that politics was going to be her path. She recruited a classmate to run for state representative and ran their campaign as an independent study for her political science degree. In 2014, she was recruited to run for state representative. At the same time, she was running a political action committee targeting young voters and serving as party staff for the state Republican Party.

“It wouldn’t have been that difficult to find political work in Minnesota,” she says. “But I had one thing that happened right after graduation that really threw me a curveball: I flew home to Texas and went on a single date with a girl that I had been talking to online.”

They hit it off and began a long-distance relationship. Surman returned to Minnesota for the election season, working what she describes as a “miserable political call-center job. One of those jobs where you make the same call for about thirteen hours a day.” She was chronically depressed. The only thing going well was her relationship. When the job ended, she returned to Texas. She and her girlfriend have since married.

The only trouble was that as she applied and interviewed for jobs in Texas, she found that her political skills didn’t really translate. “After a few months of that I realized I was in what I called ‘fun-employment,’ as a way to make myself feel better about it,” she says. “Spoiler alert: fun-employment is not fun. It’s just unemployment but adding fun to the name to make yourself feel better, and I was really getting down again.” Even though her relationship was good and she was back home with family, she didn’t have a fulfilling career. She realized she needed to make a pivot.

Surman decided to try education. She got her teaching certification and became a social studies teacher teaching US history to eighth-graders. “This was the first time that I was really able to get excited about my job, start in the morning, make it to the end of the day, and not feel miserable doing it,” she says. A few years later she was promoted and became an instructional coach mentoring other teachers.

But recently, Surman faced a couple more curveballs. “Last year, I came out as trans and it definitely has made being a teacher in Texas more difficult,” she says.

At work, her school was realigned and Surman was demoted back to a classroom teaching position. “I have a job for next year,” she says. “I know I still want to work in education if I can. I’ve already made one big pivot that was huge for me, and now I’m trying to figure out what’s next.”

Datra Oliver ’04

Johns Creek, Georgia

Datra Oliver ’04 experienced a shattering curveball at Macalester. In her junior year, her dad died. “That was my first major loss,” she says. “When we are late teenagers, young adults, there is just so much navigating of identity, new things, new problems, new adulting—whatever it is. This was just not something I was prepared for; I don’t think anyone could be prepared for it.”

Datra Oliver ’04 experienced a shattering curveball at Macalester. In her junior year, her dad died. “That was my first major loss,” she says. “When we are late teenagers, young adults, there is just so much navigating of identity, new things, new problems, new adulting—whatever it is. This was just not something I was prepared for; I don’t think anyone could be prepared for it.”

At a loss for trying to manage her grief, Oliver did something her family in The Bahamas didn’t really understand: she decided to take a break and withdraw from school. She was on track to be the first person in her household to graduate with a four-year degree. “I was on a scholarship to Macalester, and that was a really big deal,” she says. “I needed space to process my grief.” She tapped into formal mental health services, including a grief support group on campus, but struggled with her own expectations to keep performing at a high level.

She returned to Mac the following semester and, “in Macalester fashion,” worked to graduate on time, condensing a bunch of her courses, adding an economics major to her art major—and continuing to deal with her grief.

The experience led her to reflect on the idea of perfection, and on the compartmentalization of personal and professional life. “We really hold ourselves to these expectations sometimes that you go through things privately, but still need to show up in the same way in the same spaces all the time,” she says. “So, I release that. As a mom of two, I don’t subscribe to this notion of work-life balance generally. It hasn’t worked for me. Just the sound of it gives me anxiety, like walking on this tightrope of balance all the time.” Oliver reframes her choices now as “trade-offs” and seeks to prioritize what is most essential for the current season of her life.

Oliver’s second curveball was a combination of graduating into a tough economy, and another personal loss. Navigating the US job market as an international job seeker, she faced immigration questions and uncertainty. At home, her maternal grandmother had recently died and Oliver’s mom, a single parent in her 50s, was living alone for the first time in her life. Oliver decided to return home to The Bahamas.

“It was a reckoning for me,” she says. “Is this a failure that I’m returning to my home country as privileged as I was to be here in the US? There is an expectation that the US is the place to be, that’s where the dreams happen.”

But returning home, she says, was wonderful. “I heard some advice that was really good for me, and I take it forward even now,” she says. “‘Go where you are rare.’ I think a lot of times we have perceptions of what success looks like and that it has to look the same for everyone.” She stayed for two years, and helped support her mother through a family transition. She worked in the foreign service, traveled, and became interested in the law and business. She eventually completed a law degree and a few years after that her MBA. She’s now back in the states helping organizations transform, most recently with Coca-Cola in Atlanta.

“I’m not sure I would’ve gotten those types of opportunities had I only stayed in the states,” she says.

May 17 2024

Back to top