By Ashli Cean Landa

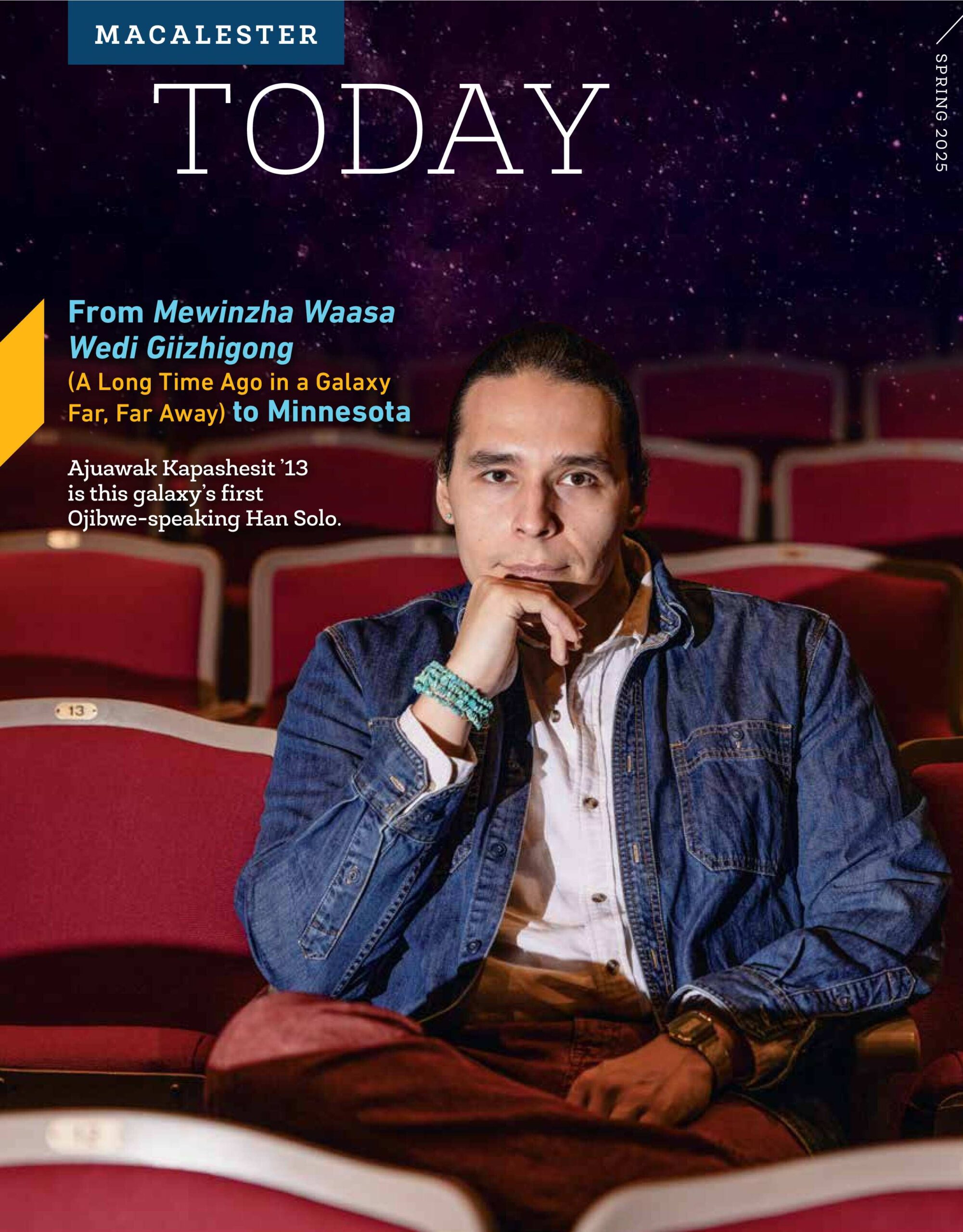

When Ajuawak Kapashesit ’13 learned he would be the voice of Han Solo for the Ojibwe dub of Star Wars: A New Hope, he couldn’t help but scream.

“I want to say it was eleven at night; I’m doom-scrolling in bed,” the writer, director, producer, and actor recalls. “And I get the email and just look at it like—oh, did all of my childhood dreams just come true?”

A dual citizen of Canada and the US, Kapashesit, who majored in linguistics at Mac, has been involved in Ojibwe and other endangered language revitalization movements since 2010. This summer’s history-making dub of A New Hope—the first Star Wars film, released in 1977—is a collaboration between Lucasfilm, the University of Manitoba, and the Dakota Ojibway Tribal Council. It’s the first major Hollywood film to be dubbed into Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe), and a milestone for efforts to spark interest in learning and preserving the language. The dub was released in select theaters around the Great Lakes region and can be heard on Disney+.

Ojibwe is classified as severely endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger list. Language loss was one objective of federal Native American boarding schools in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a key part of the cultural genocide enacted by the US against Indigenous peoples. Canada perpetrated similar acts of violence against First Nations peoples. The film aims to expose new audiences to the language in a more contemporary context, especially to the younger generations crucial to its preservation.

“Because it’s Star Wars—which is infinitely quotable—you’ll already know what a character is saying in English, and then get to learn it in Ojibwe too,” says Kapashesit.

At the August premiere in Winnipeg, Manitoba, he felt the palpable joy and excitement of cosplayers, families, and traditional dancers—including a jingle dress dancer dressed as Princess Leia—who came out to celebrate the event. “Everyone who hiked to see it on the big screen was so hyped to hear it in Ojibwe.” (Mac hosted a screening for students in November.)

Kapashesit’s day job also focuses on language recovery. He is the interim executive director at Boston-based nonprofit 7000 Languages, which creates online language-learning materials in partnership with communities who speak endangered languages.

On his own, he makes films. One of his recent documentary projects, Language Keepers, follows three Ojibwe residents of Minnesota as they use film, video games, radio, and social media to inspire new generations to learn their heritage language.

“Language Keepers was a golden opportunity to merge my expertise in linguistics and a language that the majority of filmmakers I’m interacting with don’t have any experience in,” he says. “And on the other side, most linguists I know don’t have any film experience. So I thought a lot about how to talk about language in a visual way that film people can understand but that is also accurate to concepts that linguists understand.”

He says it also was crucial to center the film in positivity.

“So many stories about Indigenous people are often pessimistic—most documentaries focus on the history around why the language is in this situation,” he says. “And that’s vitally important context, but I wanted to create something different—I wanted to tell this story in a hopeful tone.”

Kapashesit didn’t start as a linguistics major at Macalester, but in his “Endangered Minority Languages” course, he grew more and more compelled by the field as the class explored languages from communities he is a part of—Cree in northern Canada and Ojibwe in northern Minnesota.

He supplemented his linguistics studies with creative writing courses and a Hispanic studies minor. As an alum, he audited an acting course with Professor Emeritus Harry Waters Jr.

For one of his first acting gigs, he starred in Sneaky, a dark comedy set prior to the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978, produced as a traveling show in 2016 by Twin Cities-based New Native Theatre. It’s about three Native brothers who conspire to steal their mother’s body to bury her in their cultural tradition, rather than a Christian one.

“The play was talking about things that have been taken from us, like language and culture, so it’s still a relevant story to Native people,” he says. When the production traveled to the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in 2016, during the large protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline, it was especially meaningful. “The entire encampment and community were there, and we were able to perform this play for everyone standing in solidarity.”

As an actor and filmmaker, Kapashesit’s accolades include a 2018 Red Nation Film Award of Excellence—Outstanding Performance by an Actor in Leading Role; being chosen as an Indigenous Film Opportunity Fellow with the Sundance Film Institute; a Vision Maker Media Shorts Fellowship for his and co-writer/director Morningstar Angeline’s 2022 short film Seeds; and a 4th World Indigenous Media Fellowship.

Right now, he’s focusing on writing, trying out new genres like sci-fi and horror. “So if anyone wants to invest in a movie, let me know!” he laughs.

In the meantime, we can only hope we’ll catch him next in an Ojibwe dub of The Empire Strikes Back. But until then, Gi-ga-miinigoowiz Mamaandaawiziwin: May the Force be with you.

Ashli Cean Landa is a writer and editor at Macalester.

March 18 2025

Back to top