F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote, “There are no second acts in American lives,” but that pessimistic sentiment doesn’t hold sway with those over 50, who are expected to live longer and healthier lives than ever before. For many at the midpoint of their lives, creating a second act after retiring or leaving a former occupation is increasingly common.

For Macalester alumni, that means devoting their talents and passions (often developed while in college) to entrepreneurial start-ups, social activism, and artistic endeavors. They admit that starting something new later in life can be scary and certainly isn’t easy. But these innovators—who’ve found meaningful work and service a second time around—say it’s worth the risk.

Tools of the Trade

Howard Zitsman ’76, a former investment banker and current metalsmith, says that his dual careers of helping businesses make the best deals and designing high-end, one-of-a-kind belt buckles have more in common than you might think. It’s all about using and sharpening the tools at hand to craft the best result.

“Craft is a fundamental approach to everything I do,” says Zitsman, the founder of H. Perle, an Ohio-based luxury jewelry company that handcrafts belt buckles featuring natural gemstones set in sterling silver.

Zitsman’s interests in investment banking and metalsmithing reach back to childhood. His family owned both a clothing store and a jewelry store in Springfield, Ohio, so he learned the ins and outs of the retail business early on, discussing corporate prospectuses and annual reports with his grandfather. Zitsman was first exposed to the concept of craft as a boarding student at Cranbrook—a leading center of education, science, and art in Michigan known as the birthplace of mid-century design. As a beginning metalsmith, “I learned by doing, by exploring how metals react,” Zitsman says.

At Mac, Zitsman majored in psychology and continued to work with metals, making jewelry and sculpture under the tutelage of art professor Tony Caponi and in his apartment studio. While considering his future—“I’d always assumed I’d go home to run the family business,” he says—Zitsman read a Business Week profile of Chicago investment banker Ira Harris, who worked in mergers and acquisitions. Zitsman was intrigued by the idea of working with companies to solve their problems, or as he says, “applying craft to finance by using newly developing tools, valuation models, and option pricing to address corporate finance questions and problems.”

He packed away his metalsmithing tools and began a career in finance by earning an MBA at Ohio State University. He advised on billion-dollar M&A deals at Lazard Freres and Drexel Burnham in New York City, ran his own investment firm in Columbus, Ohio, and worked for the boutique firm Ladenburg Thalmann. “I loved investment banking,” he says. “There’s a real thrill in seeing the valuation you crafted being affirmed in the market.”

When the recession hit in 2008, Zitsman commuted to Washington, D.C., to help the FDIC implement the Dodd-Frank legislation, but after two and a half years grew weary of the commute.

Looking for a change, Zitsman dug up his old metalsmithing tools and began crafting jewelry. He refreshed his skills with a few classes, started buying gemstones, invested in modern machining technology, and eventually founded H. Perle. Today, he and his small production team make luxury belt buckles that retail for $2,000 to $4,000, selling their wares individually and through retail stores in Aspen, Vail, and Las Vegas.

“As an investment banker, I learned to identify opportunity and analyze markets,” Zitsman says. “I’m applying those same skills to my jewelry making, focused on creating a luxury item that can be seen as art.”

Photo by Maria Siriano

Troubled Waters

After graduating from Macalester with majors in English and dance, Mary Ackerman ’70 was determined not to work for “the man.”

“I’d gone to school in the ’60s, which was the era of being worked up about and protesting everything,” she says. “I just couldn’t work for a corporation or a big insurance agency.”

She was hired as a Macalester admissions counselor, eventually rising to the position of director of admissions, one of the only women in the country at the time doing such work. From 1979 to 1991, Ackerman created a nationally recognized student affairs program as Macalester’s dean of students. “As a student I’d worn buttons that said, ‘Challenge authority!’ and then I was working with students whose job it was to think critically and push boundaries,” she says. “I was very comfortable in that role.”

Ackerman moved on to work as a family mediator and then as director of national initiatives at Search Institute, which partners with organizations to conduct and apply research that promotes positive and equitable youth development. She retired in 2011, moving with her husband to their lake home in rural Cass County in northern Minnesota to begin “our lake chapter,” she says.

But Ackerman’s days of activism weren’t yet behind her. The move landed her in the midst of a community protesting Enbridge Corporation’s proposal to build the Sandpiper oil pipeline, which would run through wetlands, wild rice paddies, tribal lands, and across the Mississippi River. “The route was just unacceptable,” Ackerman says. The more she learned, the more she noted that none of the groups protesting were communicating with each other.

“My experience of protesting and community organizing at Macalester kicked in, as well as my career in empowering other people’s voices to be heard,” Ackerman says.

She and her husband gathered leaders from nearly a dozen advocacy organizations invested in water conservation work in northern Minnesota around their kitchen table. Those efforts launched the Northern Water Alliance of Minnesota to help activists strategize and stay informed on pipelines, aquatic invasive species, and agricultural practices that leak chemicals into the aquifers. The group succeeded in stopping the Sandpiper line, but is now fighting an Enbridge proposal to create a new east-west energy corridor in Minnesota. “Our strategy is to keep delaying until it’s just not feasible for a corporation to build a new pipeline,” says Ackerman, noting that “it’s been exciting to speak up in retirement—and amazing to know that finding my own voice has helped empower others to effect change, too.”

Photo by David J. Turner

Radical History

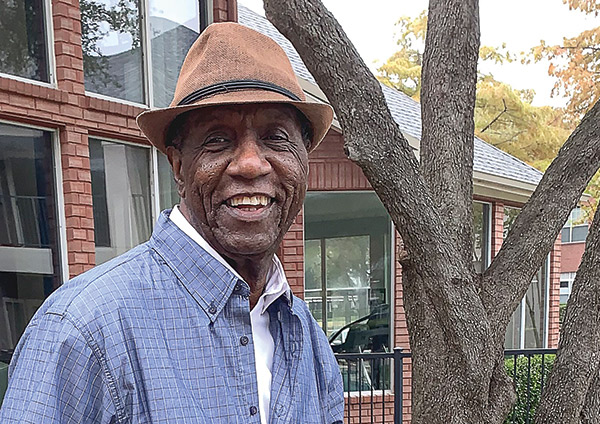

When Larry Kenneth Alexander ’73 was a child, he asked his older relatives why his great-grandfather was born a slave. “They shushed and offered no insights—they didn’t know,” he says.

Alexander went on to become a first-generation college student, majoring in history at Macalester as part of the Expanding Educational Opportunities program’s inaugural cohort. He earned a JD degree at the University of Iowa and had a distinguished career in both business and government as a commercial real estate developer and a planning commissioner for the City of St. Paul, before relocating to Texas.

But the unanswered question from his childhood stuck with him, and Alexander continued to reflect on the stories he’d heard of his great-grandfather’s life in Tennessee. “I was profoundly affected by the graphic accountings of the institutional devaluation of his humanity and by extension, all of black America,” he says.

For his second act, Alexander has turned his eye to social anthropology, critically examining the horrors of slavery through writing books, including Smoke, Mirrors, and Chains: America’s First Continuing Criminal Enterprise and King’s Native Sons, the story of James Somersett, a slave who was liberated by the English high court in 1772. Alexander’s third book, Hidden in a Book: $40 Trillion—Keep the Mule, posits that because slavery was never legally constituted, restitution—not reparations—is the proper remedy for this criminal wrong. “Early American black people were placed below the rule of law, and it’s a core ideal that laws must apply equally to everyone in a democracy, even the lowest of the low in a society,” he says. “Their legal status as Afro-Britons under British law entitled colonial blacks to liberty and due process upon the ratification of the Treaty of Paris of 1783 that ended the Revolutionary War, but instead, they were disenfranchised and then exploited as slaves.”

An advocate for reconceptualizing U.S. political culture, Alexander founded The Obsidian Policy Colloquium, a non-profit think tank with a mission to educate and advance policy discussions, initiatives, and long-term solutions. He also recently collaborated with his Macalester history professor and mentor, James Wallace professor emeritus James Brewer Stewart, to present a forum on this provocative topic during Reunion last June. They hope to host a similar forum on campus during Black History Month in February. “The thesis that U.S. slavery was not legal creates cultural and cognitive dissonance—it necessitates a rewriting of America’s historiography,” Alexander says. “This has radical implications for academia.”

Photo by G.Y. Stephens

Ancestral Ties

Sonya Anderson ’65 has never been constrained by “the standard options in life,” she says. She describes her life in four segments, all of which took some risk and required a bit of reinvention.

Segment one included majoring in public address and rhetoric at Macalester, then landing a job as a technical writer at Control Data—even though she was unfamiliar with computers at the time. “The research, questioning, and writing skills I developed through debate at Macalester helped me greatly in that career,” Anderson says.

In 1974, Anderson got married and her husband’s job brought her overseas. She spent segment two in Hong Kong, Rome, and Montreal immersed in continuing education in art history, Italian and French language, couturier sewing, and cooking and travel. “Most people wait until retirement to do things like that,” she says. “I was lucky in that I woke up and realized the learning opportunities before me.” Her time overseas also fed her curiosity about the world, first piqued in 1964, when she spent a summer working for Hilton in Tehran, Iran, through the college’s Student Work Abroad Project.

After returning to the United States, Anderson was hired at Cray Research as a technical writer and then became the company’s Midwest region analyst manager in Boulder, Colorado, thus beginning segment three. She was responsible for the group providing software technical support on Cray’s supercomputer systems at customer sites such as Los Alamos National Laboratory and the automotive industry. “It was a dream job,” she says. “I was a liberal arts-educated person managing super-talented specialized engineers.”

Segment four began after restructuring at Cray, when Anderson decided to take a year off from work to attend to family members who were in failing health. Then, 15 years ago at age 60, she began working as a home furnishings and small business consultant at the newly opened IKEA in Bloomington, Minnesota. “I told them I plan to work until I’m 80,” she says. The job has brought Anderson close to her family’s Swedish roots and she thoroughly enjoys the work, which includes interacting with people from all over the world, supporting local businesses with their furnishing needs, and helping people her age furnish newly downsized retirement spaces. “For me, it hasn’t just been about a second act, but about incorporating many experiences and interests to extend my working life,” Anderson says.

Photo by David J. Turner

Torched Earth

Gene Palusky ’79 began his career in the fine arts, struggling to pay the bills as a sculptor for about 15 years. “I realized I needed to do something else to support myself,” he says, a decision that led him to the art of home restoration. He spent the next 20 years buying, renovating, and operating old apartment buildings in the Twin Cities.

“Ultimately, working on these turn-of-the-century brownstones became my art,” says Palusky, who studied fine arts and English at Macalester and earned an MFA at the University of Wisconsin. He sold his home renovation business in 2010 with tentative plans to retire—before he learned another lesson: “I’m not the retiring type,” he says. He began to look for his next venture.

For inspiration, Palusky considered his past mission service in Equatorial Guinea and the Dominican Republic, where he’d witnessed how people—particularly schoolchildren—suffered because of a lack of reliable light and power. Kids often studied by dangerous kerosene lamps or candles and small business owners struggled with communication because they couldn’t keep their cell phones charged. “I realized that reliable light and communications could be a game changer for people in developing countries,” Palusky says.

Informed by work he’d done at Renew World Outreach, a Christian-based nonprofit that creates solar-powered tech equipment for use in global mission work, Palusky designed the XTorch (xtorch.org), a portable, waterproof, handheld device that is a rechargeable, solar-powered flashlight, lantern, and cellphone charger all in one. It can light up an entire room, and its battery can hold power for three years without a charge.

In 2015, Palusky founded EJ Case, which manufactures and distributes the XTorch. Retail sales at $60 a piece and at-cost sales to nonprofits subsidize the company’s work with humanitarian aid organizations in distributing the device in areas where it’s most needed, such as in Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. Palusky estimates EJ Case sold 1,300 XTorches domestically and 1,000 internationally last year alone. An additional 2,000 were given away.

For Palusky, the XTorch has been a labor of love, and he shares this advice with others looking toward a second act: “Regardless of how great your idea is, how profound your efforts are to help people, if you don’t love what you do, you won’t do it.”

Photo provided

By Marla Holt

Marla Holt is a freelance writer based in Owatonna, Minn.

January 21 2020

Back to top