Afrofuturism, The Next Big Thing

Contact

The Words: Macalester's English Student NewsletterSenior Newsletter Editors:

Birdie Keller '25

Callisto Martinez '26

Jizelle Villegas '26

Associate Newsletter Editors:

Ahlaam Abdulwali '25

Sarah Tachau '27

by Malcolm Cooke ’21

“I have a colleague who also always asks me, Daylanne what’s the next big thing? What’s the next big thing? I said it’s Afrofuturism, I tell you, it’s the next big thing,” Daylanne English said. She was describing the motivation behind the sci-fi infused blackness explored in the new course, “Topics in African American Literature: Afrofuturism.”

“That’s another reason for the course—it is by far the most exciting development in my lifetime, in this field.”

Of course, Afrofuturism isn’t entirely new, both as a course at Macalester but also in a much broader sense. The course is new as this is the first time it is being taught generally, instead of as a capstone.

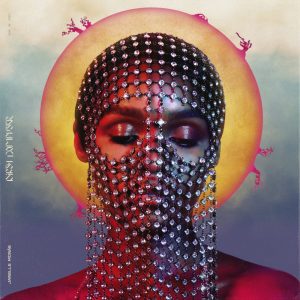

But the imagined futures, pasts, and presents Afrofuturism itself have a much longer history. The class covers works as early as the 1920 W. E. B. Du Bois story “The Comet,” to contemporary music such as Janelle Monae, and her android alter ego “Cindi Mayweather.” The breadth of this term makes it difficult to specifically define, a project Daylanne’s class has put a lot of effort into during the first weeks of class.

These examples include some similarities, a focus on the realization of new societies, employment of science fiction concepts and aesthetics, and a complicated relationship with time.

“The Comet” uses the apocalyptic destruction of New York via the titular comet to examine the dynamic between the only two surviving characters, a black man and a white woman, imagining how such interactions could grow past entrenched stereotypes in a society where white supremacist institutions and societal organizations have been completely demolished. Meanwhile Monae’s “Cindi Mayweather” is a way of explaining complicated formations of identity where they intersect with boundless new forms of technology.

But despite some similarities between identifiably Afrofuturist texts, Afrofuturism’s slippery definition must also include its myriad of different manifestations. It can appear as a genre in various forms of media, a broader form of cultural production and scholarly thought, and a more general philosophy through which to view and change the world. There are few limits on what can be described as Afrofuturist, beyond the general effort to intervene in ideas of a future society rooted in white supremacy, and replacing it with imaginations that center Blackness.

But this flexibility is part of what makes Afrofuturism so exciting. The realization that there is no set definition recognizes not only that Afrofuturism is an incredibly contemporary and still developing movement, but also that the very philosophy behind it encourages shaking loose seemingly concrete conceptions, and moving on from settled ground.

Ultimately Afrofuturism is exciting because of its focus on practicality, potentiality, and the possibility of new worlds that are radically different from the current systems of white supremacy we must reckon with. The evasive nature of Afrofuturism’s definition actually serves in its favor, providing a flexibility that allows it not only to be extremely relevant but provides a potential to grow to be even more influential.

The broad and ever-expanding nature of the topic is one of the reasons English, and her students, are so excited by it. Indeed, there is so much that can be described as Afrofuturist that even English finds it hard to keep up with the capaciousness of it as a movement, genre, methodology, philosophy, and its myriad of other forms.

This is where she draws directly on the passion and engagement of students to help expand the class into new areas. Throughout the course, students bring forth texts that would not otherwise be discussed in the class and explain how they view them to be Afrofuturist. The presentations in class are a way of exploring Afrofuturism’s wide boundaries, shining a light on the absolutely vast amount of content that can be read through an Afrofuturist lens, as well as presenting ideas for the future of the class.

“[The capaciousness of Afrofuturism] helped determine the nature of the presentations, that you would find Afrofuturist texts of all sorts that interest you, that aren’t in the syllabus. It may be that you’re determining the future, that some of those texts that you locate might end up on the syllabus,” English said.

English finds this to be an important component of research and scholarly writing outside of class as well. Especially in regards to her second book, “Each Hour Redeem: Time and Justice in African American Literature,” she found that impassioned discussion of African American literature across its entire history with students was incredibly important. The book covered a large timeline, spanning from Phyllis Wheatly’s writings at the end of the 18th Century to the present with Susan Loyd Parks. The ability to cover such a wide timespan was something that English’s unique position in the Macalester English department allowed her to do. English covers the entirety of African American literature, whereas in a larger research institution like the University of Minnesota she would be one of many African Americanists who cover different eras.

“So I had the privilege of teaching the entire African-American literary tradition to exceptionally brilliant and engaged students and I think that that enabled that book.” English said, “and I think the same is true with Afrofuturism.”

English will be on sabbatical next year, working on new projects, which will most certainly be influenced by Afrofuturist thought. With two chapters drafted, she hopes to complete the manuscript for her next book on the afterlife. English sees the idea of the afterlife as another form of future and has in mind figures who think about this that can be read as directly Afrofuturist.

In addition, English is working on a different, longer-term project deeply indebted to the spirit of Afrofuturism. This second project is specifically about Afrofuturism and uses Scalar, a software developed at the University of Southern California designed to publish long-form, book-length scholarly projects in an entirely digital format. English finds this format to be a great fit for a movement so deeply tied to media and technology, as well as providing ways to convey some of the most vibrant forms of Afrofuturism through music.

“The form of the project honors the nature of the movement. I couldn’t write or produce a scholarship about Afrofuturism if it didn’t contain sound,” English said.

The nature of the digital format also means that the project requires a great deal of effort, and won’t be finished over English’s sabbatical, but she does hope to make progress on it. But thought on Afrofuturism taking continually, utilizing technology, and over a long period of time is once again indelibly connected to the ideals of the movement as a whole. As English says, Afrofuturism is the next big thing and something with an impact that has only just started to show itself.

“My assertion is that it is broader and will have more impact potentially than even the Black Arts Movement and the Harlem Renaissance, which were extraordinarily rich important movements that had tremendous impact.” English said, “But Afrofuturism is broader in the sense of who’s part of it. It is more Feminist it is more Black Feminist. It is more consciously connected to material improvements for the world. Which something we’re studying right now, we started practically with ‘how can Afrofuturism potentially mend the world.’”