The Words, October 2017

Contact

The Words: Macalester's English Student NewsletterSenior Newsletter Editors:

Birdie Keller '25

Daniel Graham '26

Callisto Martinez '26

Jizelle Villegas '26

Associate Newsletter Editors:

Ahlaam Abdulwali '25

Beja Puškášová '26

Sarah Tachau '27

Peyton Williamson '27

Amy Thielen ’97 on Food, Culture, and Finding a Sense of Purpose

By Jen Katz ’19

Before Amy Thielen was a professional chef, memoirist, and James Beard Award-winning food writer, she was a recent Macalester graduate with an unlikely plan: to live off the grid with her boyfriend in a barebones cabin in rural Minnesota.

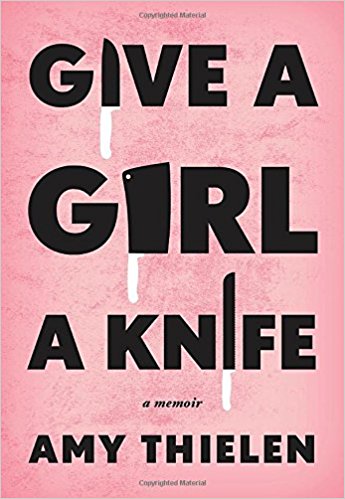

In her new memoir, Give a Girl a Knife, Thielen retells her journey beginning with cooking “with the feeling of scantness at [her] back,” using only what she harvested from her garden. Eventually, she became a line cook in some of New York City’s most prestigious and fast-paced kitchens, like Chef David Bouley’s Danube and Chef Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s 66. Along the way, she found connections between the world of haute cuisine and the more familiar realm of Midwestern food; the Austrian spaetzle she prepared in Chef Bouley’s kitchen recalled the egg noodles her mother used to make.

Thielen, who now works as a freelance food writer, will return to Macalester on November 9 for a lecture about her career and a reading from Give a Girl a Knife in Weyerhaeuser Board Room at 7:00 p.m. In advance of her visit, The Words presents an interview with Thielen about her time at Macalester, her career, and some advice for students. This interview has been edited for brevity.

The Words: How did your experience as a Macalester English major inform your journey as a chef and author?

Amy Thielen: I think that my Mac education encouraged me to read and think beyond the canon, and pursue connections between disciplines—literature and cooking, in my case—that a more rigid school might not foster. Above all, my teachers valued critical thinking, originality, fluency, and a strong writing voice—all skills I use every single day.

My professors assigned an insane amount of reading, and I believe that the quality of your writing is directly related to how many words you’ve vacuumed up and consumed in your lifetime. High-minded or low-brow or trashy-pop, it really matters not. It’s the volume of words that counts the most. Although the diversity of voices in our reading lists almost certainly also gave me depth.

Going to a liberal arts college felt almost like an extravagance; I could indulge in my reading habit to the hilt. I didn’t have to split up my attention with math or science, subjects I hated. (Although I did take Math for Poets. My project was on billiards, and my partner and I did all of our research at the pool table in the Turf Club.) I do think that writers, and artists of any stripe, need to feel that it’s okay to admit that there’s pleasure in what they do. In the real world, where I’m writing for money, I need to continually tap into my hedonistic love for writing, because it’s hard work, and sometimes deadlines are not reason enough. Ultimately, it’s my love for it, the pleasure I take in words and sentences and sentiments, that makes me sit down and begin. And incoming emails that flash my bank balance are what make me finish.

TW: What class, professor, or experience at Macalester was most formative for you during your time as a student?

AT: Robert Warde was my hero during my Macalester years. I begged and pleaded with him to let me to join his senior seminar on Lolita when I was just a junior, because I was obsessed with Vladimir Nabokov. The wordplay! The narrative structure! What English major wasn’t? He let me in, and then proceeded to upend all my assumptions about Lolita and ruin my simple worship for it in all of the best ways. He wasn’t a pusher with his knowledge; he made us work for our own conclusions. Halfway through the seminar the sickness of the pedophilia dawned on me like an icy blanket, and ever after, I’ve subjected all art to the Lolita principle: just because something’s beautiful and seductive doesn’t make it morally right. Nabokov was a trickster; he knew he was seducing the reader with his language, and that art possesses the power to subvert our better judgment.

In New York, when my artist-husband and I went to galleries, I remembered that. Paul McCarthy, he, and Nabokov were doing the same thing. It didn’t diminish the importance of the work, but it gave my analysis of it more depth. And years later, when I began writing stories about the foodways and habits of my rural neighbors for my cookbook, I remembered that as a writer I had a responsibility to render their stories with honesty and fairness, but also nuance. People are complicated. Even in nonfiction it’s important to allow your characters to be real and loose-jointed.

TW: What advice do you have for Macalester students beginning to cook for themselves, often with limited time and money?

I know this sounds snobbish, but you should really invest in big equipment: a large cutting board, a wide pan, a decent strainer, a big sharp knife. You can make do with what you’ve got and sometimes get lucky, but you can’t consistently cook well with crappy serrated knives and tiny cutting boards and little pans. Not that you do. I’m just saying, it’s not possible.

Beyond that, play. Now’s the time to explore and make mistakes. And pay attention to your hunger. If you can really zero in on what you’re hungry for at that moment—fat dates or crispy potatoes or raw cabbage or braised falling-apart beef—health and balance will naturally follow.

Want to hear more from Amy Thielen? Make sure to attend her talk at 7:00 p.m. on November 9 in Weyerhaeuser Boardroom.